by Jessica Heim

This paper explores the nature of amateur and professional astronomers’ attitudes towards and relationship with the night sky. This research uses a mixed method approach, utilizing both interviews and questionnaire responses. It examines how respondents feel about the night sky, what it means to them, and their thoughts about light pollution. It was found that a high percentage of individuals surveyed expressed that they have an emotional attachment to and feel as sense of connection with the night sky. Many elaborated on why being able to view the night sky is important to them and enriches their lives. Respondents also frequently noted seeing increasing levels of light pollution, and several expressed concern about how lack of access to dark skies could affect future generations. This paper finds that for the population surveyed, the ability to experience the dark night sky is essential for wellbeing.

Introduction

Tim Ingold argues that since contemporary humans live so much of their lives indoors, they have lost their connection to the world outside of enclosed spaces, the outdoors.[1] However, Campion argues that all civilizations have felt a sense of awe about the sky.[2] This paper aims to examine whether contemporary people still experience a sense of connection to the sky. Specifically, it explores the nature of amateur and professional astronomers’ attitudes towards and relationship with the night sky. It endeavours to look into how these people feel about the night sky, their place in the universe, and issues relating to the night sky, such as light pollution. This work builds upon previous research in this area. This includes the work of William Kelly, who developed the ‘Noctcaelador Inventory,’ a list of questions designed to discern individuals’ degree of connection to the night sky.[3] It also references Jarita Holbrook’s findings on individuals’ relationship with the sky based upon her ‘The Sky in Our Lives’ survey.[4] In addition, it connects to the work of Ada Blair, whose research focused upon the role of the sky in the lives of people living on the Dark Sky Island of Sark.[5]

This project uses a mixed method approach as suggested by Monique Hennicnk, et al.[6] It uses a combination of semi-structured interviews and an online questionnaire distributed to individuals interested in the night sky, many of whom were members of local amateur astronomy organizations. It was found that the majority of people surveyed do indeed have a strong connection to the night sky, and many shared detailed explanations of how viewing the night sky has affected their lives in a positive way.

Literature Review

In his paper, ‘Earth, Sky, Wind, and Weather,’ Ingold argues that due to so much of their time being spent indoors, contemporary people think differently from those from societies in which more time was spent outdoors. He believes that all this time indoors creates ‘difficulty in imagining how any world we inhabit could be other than a furnished room.’[7] However, Campion has a different perspective, stating that there is no ‘society that does not express at least some fascination with the sky and its mysteries.’[8] He argues that such ‘awe of the heavens’ can be seen to ‘be a universal human attribute.’[9] Thus for Campion, the sky holds a place of importance in the lives of ancient and modern peoples alike.

There has not been a great deal of research done on the relationship of contemporary humans with the night sky. In particular, there is a dearth of research on astronomers’ relationship with the night sky. Jaritia Holbook has done some of the pioneering work in this area. She has used her ‘The Sky in Our Lives’ survey to examine attitudes and beliefs toward the sky of professional and amateur astronomers. [10] Among some of her preliminary findings were that contrary to popular conceptions of astronomers, in the population she studied, she did not find the majority of astronomers to be agnostics and atheists.[11] Regarding the purpose of her research, Holbrook states, ‘as with ancient people, contemporary people have a relationship with the night sky. However, we do not know the details of that relationship,’ hence her continuing research on this subject. [12]

Ada Blair has also chosen to study the relationship between contemporary humans and the night sky, albeit a different group, residents of the Dark Sky Island of Sark. In her research, she interviewed people from Sark to uncover the ways in which having continual access to a dark night sky impacts their lives. There has been much more research done, as Blair observes, on the importance of interaction with nature in maintaining wellbeing than on studying similar effects resulting from access to a dark sky. For example, Richard Louv, a journalist who has written extensively about the benefits of regular contact with nature for children and communities, coined the term ‘nature-deficit disorder’ to describe negative consequences of lack of contact with the natural world upon physical, mental and emotional health.[13] Blair concludes that interaction with dark skies, like other parts of nature, has a positive effect on wellbeing.[14]

Psychologist William Kelly has developed the ‘Noctcaelador Inventory’ (NI), a list of ten questions intended to provide a means of measuring individuals’ interest in the night sky. In this inventory, respondents are asked to rank the extent of their agreement with each of the ten statements on a one to five scale, ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. Kelly and Bates found that when comparing the NI scores of astronomical society members to those of controls, the astronomical society members scored significantly higher, thus providing support for the effectiveness of this scale in measuring connection to the night sky.[15]

There is also some nature writing which touches upon issues of light pollution or lack thereof and its relationship to society. For instance, Paul Bogard has written on the subject of increasing light pollution and how the abundance of artificial lighting at night has detrimental effects on the health of both humans and ecological systems.[16] In addition, in his guide to astronomy in the U.S.’s national parks, Tyler Nordgren discusses reasons why dark skies should be preserved and voices his concerns about the negative consequences which may result if they are not.[17] Both argue that losing the night sky would be a great loss to humanity and argue for changes to the way people light up their cities and neighborhoods.

Methodology

This project uses a combination of questionnaire responses and semi-structured interviews. Henneck et al suggest using a mixed method approach, as does Alan Bryman, who gives examples of research involving both questionnaires and interviews.[18] As Judith Bell observes, though there are benefits to interviews, such as the ability to ask the interviewee further questions and to clarify responses, there are also downsides, such as the amount of time it takes to conduct and transcribe interviews and increased difficulty in analysis.[19] Thus for this research, I decided to design an electronic questionnaire, which would be my primary data collecting instrument and also do three interviews.

Though the individuals I interviewed all expressed an interest in astronomy and the night sky, they each came from a different background. One of the interviewees, Annette Lee, is a professional astronomer and university professor in her 40’s. The second interviewee, Ian Bernick, is a very avid amateur astronomer in his 30’s, and the final interviewee, Jessica Bernick, also in her 30’s, is Ian’s wife. She indicated that I would get a ‘layperson’s perspective’ from her, as while she enjoys the night sky, she does not share the same level of enthusiasm for it as her husband does. Thus I felt that the individuals I interviewed were representative of the spectrum of perspectives I was aiming to examine in my research.

In designing my research questions for both the questionnaire and interviews, I have based many of my questions on those used by Holbrook and Blair in order to facilitate an easier comparison of my findings with theirs. Both my questionnaire and interview questions can be found in appendices at this end of this paper. For the questionnaire, Google Forms was used in order to facilitate ease of completion by respondents. I distributed the questionnaire to individuals on the general e-mail list of a large astronomy society in my state (Minnesota) as well as posted it on their online forum. In addition, it was distributed to members of the smaller, regional astronomy club in my area. I also e-mailed the questionnaire link to a number of individuals I know personally who are very interested in viewing the night sky, and some of these people forwarded the survey link to other night sky enthusiasts they knew. A total of fifty individuals, including the three interviewees, completed the questionnaire.

The questionnaire consisted of five sections and contained a combination of list, multiple choice, Likert scale, and open questions. Though, as Bell observes, open questions can prove more challenging to analyze, I felt it was important to include a number of these in order to enable respondents to better share their stories and other personal experiences relating to the night sky.[20] The first section of my questionnaire gathered demographic information, while the second asked about respondents’ activities in relation to the night sky, such as whether they have used or own a telescope. The third section consisted of Kelly’s ten NI questions, section four asked respondents about their thoughts and feelings about the night sky, and section five focused upon respondents’ thoughts and attitudes about dark skies and light pollution. It was estimated that the questionnaire should take approximately fifteen minutes to complete.

Reflexive Considerations

I have been a planetarium educator for about five years, presenting astronomy education programs to school groups and the general public. I greatly enjoy learning about new discoveries in astronomy, and I also have a strong interest in observing the night sky, typically viewing it nightly. Being able to observe the night sky is extremely important to me, and I find the rapidly increasing levels of light pollution where I live to be quite distressing.

I would consider myself somewhat of an insider to my target groups. The individuals I interviewed are people I know and interact with frequently. I am also a member of both of the astronomy organizations to which I distributed my questionnaire. In addition, I know a number of the amateur astronomers who received my survey. Yet, I would also consider myself an outsider to these astronomical organizations, as I have not been a member of either of them for long (less than one year), and thus, I have not met the majority of the people who completed my survey.

Ethical considerations

All individuals receiving the questionnaire were provided an explanation of the nature and purpose of this research. They were informed that by completing the questionnaire, they were consenting to their data being used in my research and were assured that they would be anonymous. In order to begin the survey, respondents had to first click, ‘I agree’ to this statement. Interviewees were likewise informed as to the nature of the research, and they each signed a release form. They opted to have their actual names used in this paper. Thus I have used pseudonyms to refer to all questionnaire respondents but have used the real identities of my interviewees in this paper.

Findings/Discussion

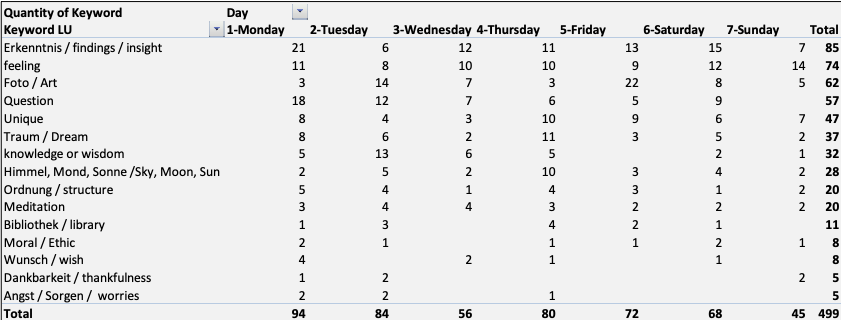

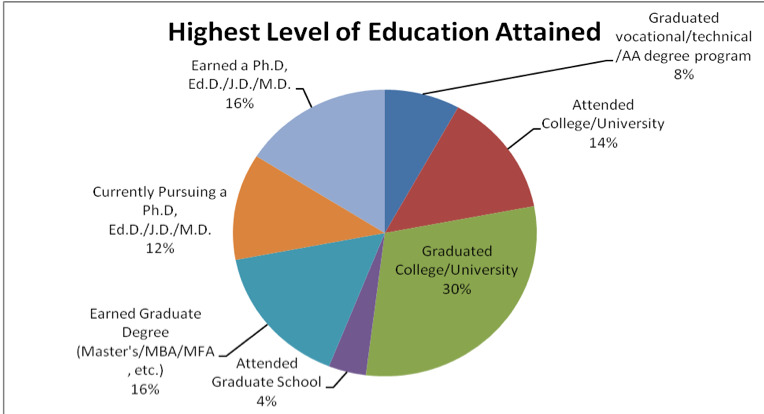

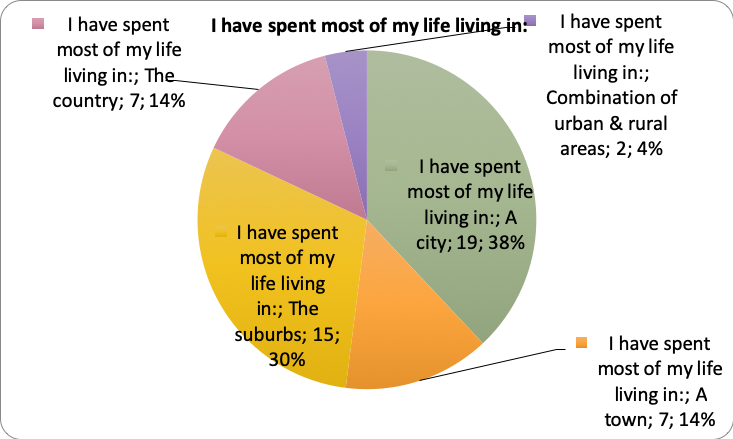

I found that a high percentage of respondents were white, male, and highly educated, with nearly half having a Masters degree or higher. They also tended to be older, with the median age being 57, and all but five lived in Minnesota. Some lived in more urban areas, while a much smaller percentage lived in the country. The majority indicated that they were amateur astronomers, though eight marked ‘None of the Above’ when asked to indicate their connection to astronomy. Given the methods I used of distributing the survey, regardless of how respondents described themselves, all had an above average interest in the night sky.

| Population | Number of People |

| Male | 38 |

| Female | 11 |

| Blank | 1 |

Figure 1: Population

| Ethnicity | Number of People |

| White/Caucasian | 42 |

| Mixed Race | 3 |

| Indian | 1 |

| Pakistani American | 1 |

| Blank | 3 |

Figure 2: Ethnicity

| Astronomy Connection | Number of People |

| astronomer | 4 |

| Amateur astronomer | 37 |

| Astronomy Grad student | 1 |

| None of the Above | 8 |

Figure 3: Astronomy Connection

| Age | Number of People |

| 20-29 | 5 |

| 30-39 | 4 |

| 40-49 | 4 |

| 50-59 | 12 |

| 60-69 | 13 |

| 70-79 | 7 |

| 80-89 | 1 |

| ‘Old’ | 1 |

| Blank | 3 |

Figure 4: Age

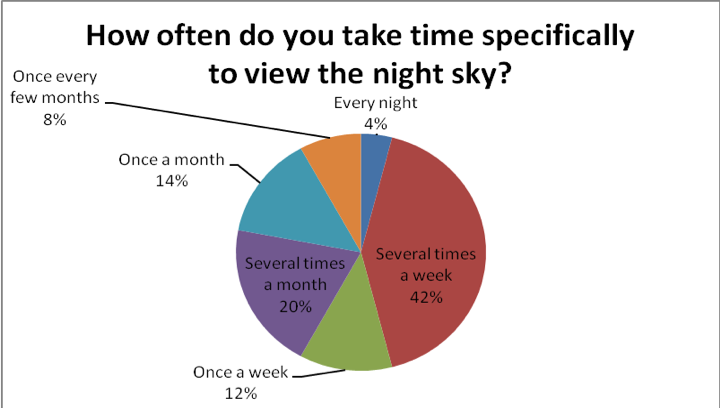

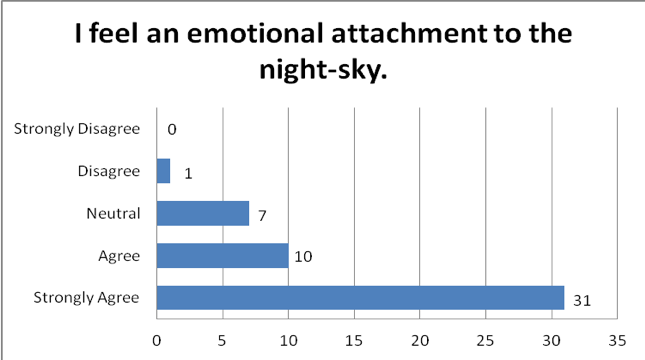

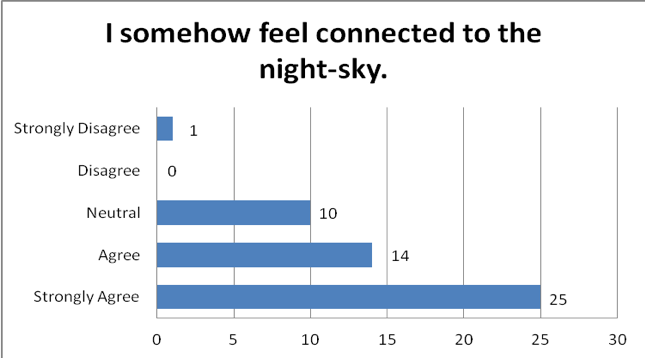

As expected, it was found that the majority of people in this study regularly engaged with and felt a sense of connection to the night sky. Fifty-eight percent indicated that they took time to view the night sky one or more times a week, with an additional 20% percent saying that they typically do this several times a month. Every respondent had used a telescope to view celestial objects, and seventy-two percent owned one or more telescopes (many owned several). Likewise, the results from Kelly’s NI questions showed that many respondents showed a strong connection to the night sky. For example, 84% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they ‘feel an emotional attachment to the night sky,’ and 78% agreed or strongly agreed that they ‘somehow feel connected with the night-sky.’ So it appears that for this group of people, a personal connection to the night sky is indeed important, and in the remainder of this paper, I will explore the nature of this relationship in more detail.

Though a few respondents indicated that experiences as an adult, such attending a star party, sparked their interest in night sky observation, the vast majority of respondents indicated that their connection to the night sky began in childhood, and many shared memorable experiences with the sky from their early years. For instance, Samuel, a 25 year old physics graduate student shared, ‘I come from rural India and it’s very common to sleep outside under the night sky in summer days. I remember my grandparents telling fascinating stories about constellations while pointing them to me during those times.’ Similarly, James, a 52 year old Minnesotan, indicated that his earliest memories of the night sky were from looking up from his backyard ‘as a WEE tot.’ He went on to share a memorable experience from his early teens:

I received my first telescope on Christmas Eve at age 14 … I put it together and took it out into the cold Minnesota night: jammies, parka and boots. It was 2 am. I found the brightest thing in the sky and pointed at it … it was Jupiter. I could see the cloud belts and the Galilean moons. I couldn’t believe I was seeing it with my very own eyes! I ran inside and woke my mom; told her she had to come and see it. She was incredulous. “I can’t believe it,” she shrieked and giggled with delight. Tears were streaming down her cheeks. That night changed my life.

The correlation with being able to engage with the night sky as a child and lifelong interest in both observation and in astronomy is noted by Nordgren, as he observes, ‘Nearly every astronomer I know, can point to a transformative moment as a child, be it a first look through a telescope, a meteor shower, or the sight of the Milky Way on a night spent camping under the stars.’[21] Nordgren points to the importance of firsthand observation in igniting an interest in the night sky and astronomy.[22] This was a theme that came up repeatedly in my research. When describing what inspires him to look through his telescopes, Ian noted, ‘you can see it firsthand, and I think that’s kind of special.’ Thus it appears that, though photographs taken by space telescopes are certainly engaging and can perhaps engender further appreciation of the wonders of the universe, it is the personal, firsthand experience with the night sky, particularly as a child, which has the deepest and most transformational effect upon a person and creates a sense of connection to the cosmos.

Respondents elaborated on why viewing the night sky is meaningful for them. For many, there was the joy of learning and of sharing with others. Some said viewing the night sky brought about feelings of connection to the universe, and others mentioned it was beneficial for their psyche. As James explained, ‘It’s good for my soul. It centers me.’ Similarly, Julia, a 22 year old graduate physics student, noted, it ‘allows me to experience emotions that I rarely experience elsewhere.’ Thus it seems to be a combination of the excitement of learning, connecting with the world beyond the earth, and the emotions this engenders which draws many to observe the night sky.

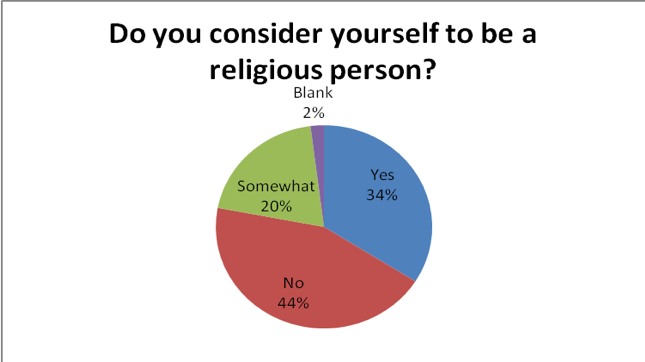

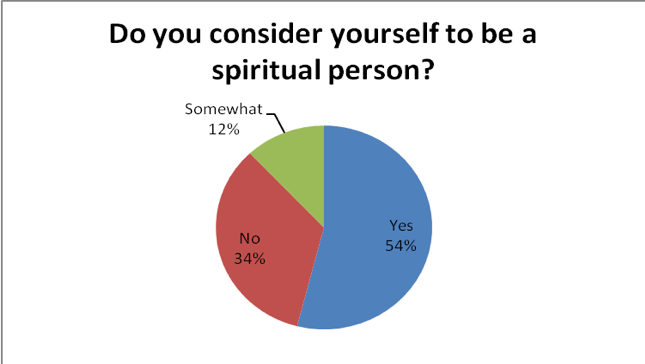

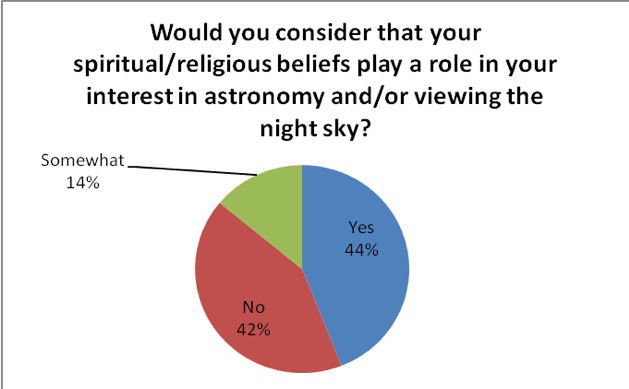

Respondents were asked to specify their religious or spiritual tradition. Because this was an open question, I got a great variety of responses. Some were challenging to neatly classify into a particular category. For example, one individual said that he was ‘Protestant, but heading towards Buddhist;’ another stated he was ‘between Catholic and atheist.’ Notwithstanding, I found that more respondents declared religious or spiritual traditions than did not. In addition, more than half of respondents indicated that religious and spiritual concepts were important components of their interest in the night sky, and many chose to elaborate upon the reasons why. Julia indicated her belief in God as creator of the universe and noted, ‘That’s one of the reasons I chose to study physics in college. I’ve always feel that by learning how nature works, I’m also learning the mind of God.’ Similarly, Dave, a 50 year old Minnesotan, noted that he finds that looking at the sky ‘strengthens religious belief.’ Thus for such individuals, viewing the sky, understanding the workings of the universe, and deepening spiritual beliefs go hand in hand. Also, several people who identified themselves as agnostic or atheist indicated that their spiritual/religious beliefs played a role in their interest in the night sky. For example, Sally, a 62 year old secular humanist, indicated that she experiences ‘transcendent feelings’ and that she is ‘a part of the universe’ when she is in nature or looks at the night sky, while Derek, an agnostic 71 year old, notes that he considers himself to be a spiritual person and states that in observing the night sky there is ‘a possible connection to a higher and lasting spirit.’ Thus, for many respondents, there was definitely a ‘spiritual’ component relating to their interest in the heavens.

| Religious Tradition | Number of people |

| Christian or specified a specific denomination | 17 |

| Baha’i | 2 |

| Messianic Jewish/Hebrew roots | 1 |

| Muslim | 1 |

| Spiritual, but non-aligned, lifelong seeker, Pagan, etc. | 6 |

| Currently between traditions | 3 |

| Raised Christian, but not very religious | 2 |

| Atheist and/or agnostic | 13 |

| None | 2 |

| Blank | 3 |

Figure 10: Religious Tradition

These results support Holbrook’s observation, based upon her research with astronomers, that not all interested in astronomy are atheists, and indeed, many such people do claim a religious tradition.[23] Holbrook also mentions that she received strong criticism from some atheist astronomers regarding her findings.[24] In my research, I likewise encountered a few individuals who were quite upset to be asked anything about religion. Though most were more than happy to discuss their thoughts about religion and spirituality, regardless of what these beliefs were, a couple were not. Josh, a 64 year old atheist, inquired, ‘Why does religion have anything to do with this survey.’ Similarly, when asked to indicate his religious or spiritual tradition, Mike, a self described ‘old’ individual, exclaimed, ‘religion when we’re talking about science? didn’t religion say that the earth was the center of everything?’ Thus by bringing up the topic of religion in the context of astronomy and the night sky, like Holbrook, I encountered some opposition.

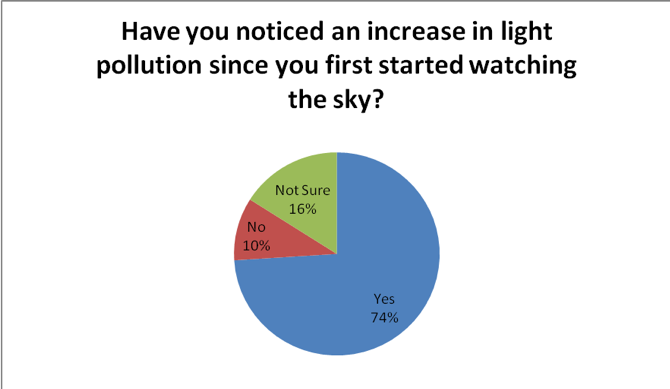

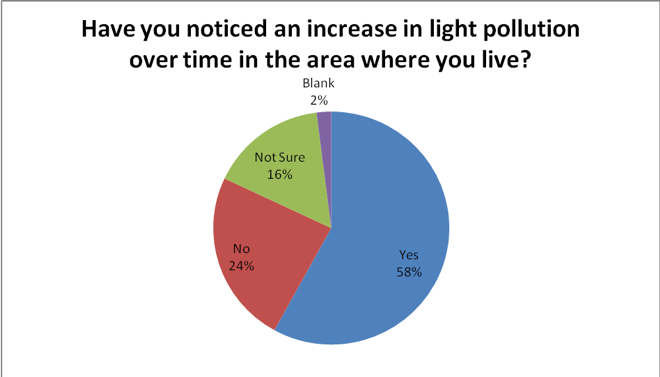

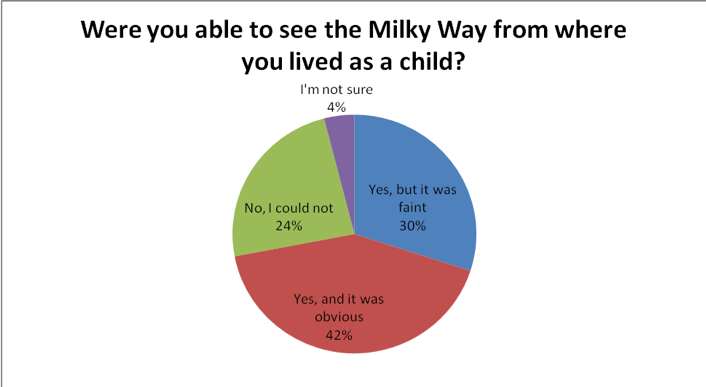

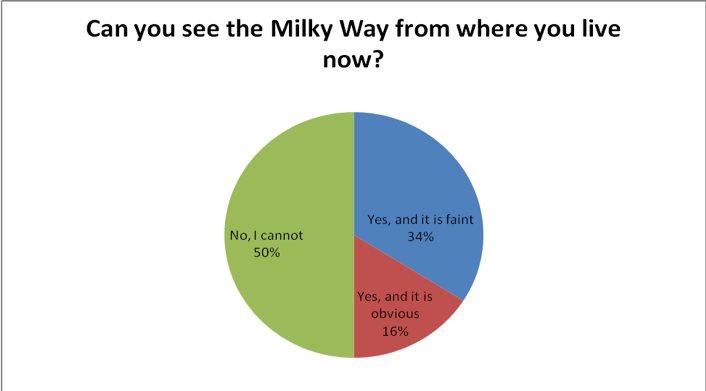

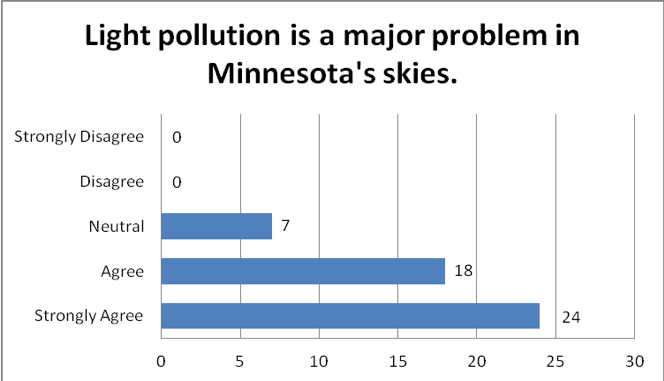

A high percentage of respondents had noticed an increase in light pollution over time, and many also noted diminishing viewing conditions where they lived. Additionally, though 72% could see the Milky Way from where they lived as a child, only 50% can see it from where they live now. One might wonder whether this could be explained by a childhood in the country followed by a move to a city as an adult, yet there were respondents who discussed how much darker the skies were in places they frequented in years past than those same locales are today, and some described relatively urban locations as having quite good viewing conditions when they were younger. Though this is certainly a marked decrease, the fact that half of those surveyed can still see the Milky Way at all where they live, indicates that the overall light pollution levels in Minnesota may not be as high as elsewhere in the country, as according to Fabio Falchi, about 80% of North Americans cannot see the Milky Way from where they live.[25] Eighty-six percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that ‘Light pollution is a major problem in Minnesota’s skies.’ So it is evident that these individuals are keenly aware of changes in the night sky.

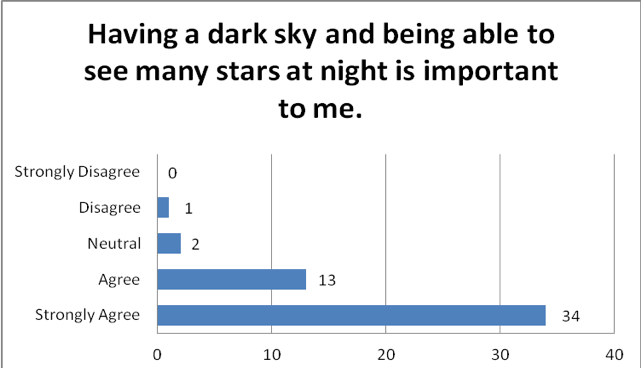

When asked how the increase in light pollution made them feel, ‘sad’ was by far the most common response. Some were angry, and one man said increasing levels of light pollution where he lived made him feel ‘disappointed’ and ‘robbed.’ Nearly all indicated that they found light pollution to be upsetting. Ninety-four percent agreed or strongly agreed that ‘Having a dark sky and being able to see many stars at night is important to me.’ To give an example of this, Ian shared that before purchasing a home, he examined dark sky maps to assist him in choosing a location with good viewing conditions. Similarly, Annette indicated that if she moved, she would try to go somewhere the sky was darker. So it is clear that for many respondents, the prospect of an impaired view of the night sky was upsetting indeed.

Respondents were asked to describe how they felt when viewing a very dark night sky and contrast this with a light polluted view. Many gave vivid descriptions of their experiences with a dark sky, and it was clear that for a lot of people, viewing such a sky not only provided more interesting and beautiful views, but brought about radically different emotions. When viewing a dark sky, respondents reported feeling, ‘in awe,’ ‘happy,’ and ‘exhilarated.’ In contrast, emotions felt when looking at a light polluted sky included, ‘feelings of loss and disappointment’ ‘indifferent,’ and ‘frustrated.’ Several described viewing the dark sky as a much more tactile experience. In describing the sky in a remote area, Ian noted it ‘just seemed like you could almost touch it.’ Henry, a 28-year-old physics graduate student, gave a similar description, ‘It’s a completely different world. When you’re in a location with a truly dark sky, you feel like you’re being sucked into the sky.’ Bogard describes the feeling of falling into the stars, termed ‘celestial vaulting,’ and notes that such an experience is only possible in a truly dark sky. [26] Thus viewing a dark sky enables a vastly different experience than observing from a light polluted area.

Many respondents lamented the loss of darker skies, but a few were particularly poignant in their descriptions of how important access to a dark sky is to them. Annette shared, ‘It’s like the difference between eating junk food, and using that to sustain you, or eating a really good, high protein, nutritious, good healthy meal. The dark sky is like the healthy meal. The junk food is like being in a light polluted area.’ She likened lack of access to a dark sky for an extended period of time to being a boat without an anchor, getting thrown about by the waves. When asked what prompts her to look skyward, she responded, ‘I think it would be like saying, “What prompts you to breathe?” ‘ For Annette, it is clear that regular access to a dark sky is essential for health and wellbeing. The feelings shared by her and other respondents about how differently dark and light polluted skies make them feel offer strong support for Blair’s conclusion that dark skies do indeed benefit wellbeing.[27]

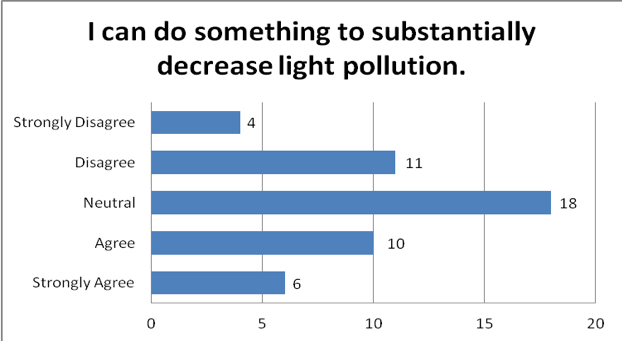

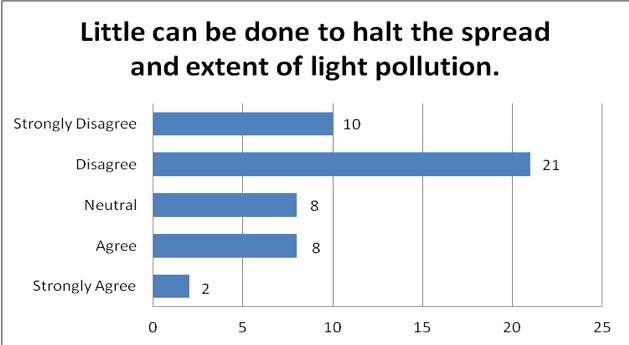

Though there was much agreement about the existence of light pollution and the fact that it was upsetting, there was less consensus about whether this state of affairs could be altered.

Only 32% agreed or strongly agreed that ‘I can do something to substantially decrease light pollution.’ However, 63% disagreed or strongly disagreed that ‘Little can be done to halt the spread and extent of light pollution.’ So while nearly two thirds believed that something can be done to stop light pollution, about half as many thought that they personally could create change. Those who shared their experiences trying to educate city officials about dark sky friendly lighting expressed frustration. Remarks included, ‘Politicians are idiots’ and ‘It’s tough to do anything about it because people think you’re a tree hugging nut job.’ Perhaps feelings of defeat resulting from trying to make a change in lighting could be responsible for fewer people thinking that they can do something to effect change, yet this seems unlikely to be the major reason, as many more people disagreed that they could do something than indicated they had actually tried. So it appears that the prevalent belief is that there is a problem, but somebody else will solve it.

Several people expressed concern about negative consequences for society resulting from a loss of contact with the sky. George, a 53 year old Minnesotan, observed that the ‘majesty of dark sky was common experience for most of human history,’ and he pondered the effect the loss of it will have on humanity. Similarly, Jane, a 27 year old mother of three, was concerned about whether future generations will know and appreciate the sky, and suggested ‘more outreach programs for children,’ as if ‘children were introduced to astronomy like I was at a young age there would be a better appreciation for what is being lost.’ Nordgren likewise expresses concern about what will happen if the night sky is obscured for most of humankind. ‘With no night sky to fire the imagination of potential young Einsteins or Sagans, where do the new scientists come from?’ he asks.[28] He argues that without the ability to experience the night sky first hand, ‘public interest in astronomy will simply fade away. After all, how do you convince someone to care about a forest wilderness who has never wandered in a meadow, climbed a mountain, or even seen a tree?’[29] This is exactly the argument Louv makes, that if children grow up without contact with the natural world, they will not care to protect it.[30] Thus it is suggested that not only does the loss of dark skies have the potential to diminish individual wellbeing, it may also create negative social consequences as well.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to explore the nature of amateur and professional astronomers’ relationship to and feelings about the sky. It was found that my interviewees and questionnaire respondents do indeed have a strong interest in and connection to the night sky. Thus for at least this particular subset of contemporary people, contact with the sky is still an integral component of their lives. Respondents reported viewing the night sky on a regular basis, and most indicated strong emotional connections to the sky. In addition, many noted spiritual or religious aspects relating to their interest in the night sky. It was also found that, for many people, contact with a dark night sky brings about a sense of wellbeing while conversely, light pollution brings about feelings of sadness and loss. Nearly all agreed that light pollution is a problem in Minnesota, and though there was less consensus as to whether light pollution could be reduced, concerns were voiced that if light pollution continues to increase, the loss of the night sky will be a major loss for humankind. Campion neatly sums up these concerns: ‘Light pollution cuts off our heritage, reduces our wellbeing and deprives us of contact with a huge part of our natural environment.’[31] Perhaps further research and public knowledge of both the negative effects of light pollution as well as the benefits to be had from dark skies will eventually bring back the night sky for millions of people who have never seen a truly dark sky and will allow future generations to continue to marvel at the wonders of the universe.

Bibliography

Bates, Jason and William Kelly, ‘Criterion-Group Validity of the Noctcaelador Inventory Differences Between Astronomical Society Members and Controls ,’ Individual Differences Research, 3 (3), Hogrefe Publishing, (2005), 200-203.

Bell, Judith, Doing Your Research Project: A guide for first-time researchers in education, health and social science, 5th edn (Berkshire, England: Open University Press, 2010).

Blair, Ada, Sark in the Dark: Wellbeing and Community on the Dark Sky Island of Sark (Ceredigion, Wales: Sophia Centre Press, 2016).

Bogard, Paul, The End of Night: Search for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light (London: Little Brown and Company, 2013).

Bryman, Alan, Quantity and Quality in Social Research (London & New York: Routledge, 1988).

Campion, Nicholas, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions (New York & London: New York University Press, 2012).

Campion, Nicholas, The Dawn of Astrology: A Cultural History of Western Astrology, Volume 1: The Ancient and Classical Worlds (London & New York: Continuum Books, 2008).

Campion, Nicholas, Preface to Sark in the Dark: Wellbeing and Community on the Dark Sky Island of Sark, by Ada Blair (Ceredigion, Wales: Sophia Centre Press, 2016) pp. xvii – xxvii.

Falchi, Fabio, Pierantonio Cinzano, Dan Duriscoe, Christopher C. M. Kyba, Christopher D. Elvidge, Kimberly Baugh, Boris A. Portnov, Nataliya A. Rybnikova and Riccardo Furgoni, ‘The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness,’ Science Advances, 2 (6), American Association for the Advancement of Science, (2016).

Hennick, Monique, Inge Hutter, and Ajay Bailey, Qualitative Research Methods (London: Sage Publications, 2011).

Holbrook, Jarita, ‘How Odd is Odd? Studying astronomers,’ (paper presented at the Conference of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture, Lubljana, 2012).

Holbrook, Jarita, ‘Sky Knowledge, Celestial Names and Light Pollution,’ (unpublished MS, University of Arizona, 2009).

Ingold, Tim, ‘Earth Sky, Wind, and Weather,’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13 (2007), 19-38.

Kelly, Willam, ‘Development of an Instrument to Meausure Noctcaelador: Psychological Attachment to the Night-Sky,’ College Student Journal, 38 (1), Project Innovation, (2004), 100-103.

Louv, Richard, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2005).

Nordgren, Tyler, Stars Above, Earth Below: A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks, (Chichester, UK: Praxis, 2010).

[1] Tim Ingold, ‘Earth Sky, Wind, and Weather,’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13 (2007), 19-38, (p. 29).

[2] Nicholas Campion, The Dawn of Astrology: A Cultural History of Western Astrology, Volume 1: The Ancient and Classical Worlds (London & New York: Continuum Books, 2008), p. 5.

[3] Willam Kelly, ‘Development of an Instrument to Meausure Noctcaelador: Psychological Attachment to the Night-Sky,’ College Student Journal, 38 (1), Project Innovation, (2004), 100-103.

[4] Jarita Holbrook, ‘Sky Knowledge, Celestial Names and Light Pollution,’ (unpublished MS, University of Arizona, 2009).

[5] Ada Blair, Sark in the Dark: Wellbeing and Community on the Dark Sky Island of Sark (Ceredigion, Wales: Sophia Centre Press, 2016).

[6] Monique Hennick, Inge Hutter, and Ajay Bailey, Qualitative Research Methods (London: Sage Publications, 2011), pp. 52-58.

[7] Tim Ingold, ‘Earth Sky, Wind, and Weather,’ p. 29.

[8] Nicholas Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions (New York & London: New York University Press, 2012), p. 1.

[9] Campion, The Dawn of Astrology: A Cultural History of Western Astrology, p. 5.

[10] Jarita Holbrook, ‘Sky Knowledge, Celestial Names and Light Pollution,’ (unpublished MS, University of Arizona, 2009).

[11] Jarita Holbrook, ‘How Odd is Odd? Studying astronomers,’ (paper presented at the Conference of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture, Lubljana, 2012), p.4.

[12] Holbrook, ‘ How Odd is Odd? Studying astronomers,’ p.3.

[13] Richard Louv, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2005), p. 34.

[14] Blair, Sark in the Dark, p. 147.

[15] Jason Bates and William Kelly, ‘Criterion-Group Validity of the Noctcaelador Inventory Differences Between Astronomical Society Members and Controls ,’ Individual Differences Research, 3 (3), Hogrefe Publishing, (2005), 200-203, (p. 202).

[16] Paul Bogard, The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light, (New York: Little Brown and Company, 2013).

[17] Tyler Nordgren, Stars Above, Earth Below: A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks, (Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing, 2010).

[18] Monique Hennick, et al, Qualitative Research Methods, pp. 52-58; Alan Bryman, Quantity and Quality in Social Research, (London & New York: Routledge, 1988), pp. 371-139.

[19] Judith Bell, Doing Your Research Project: A guide for first-time researchers in education, health and social science, 5th edn (Berkshire, England: Open University Press, 2010), p. 161.

[20] Bell, Doing Your Research Project, p. 141.

[21] Nordgren, Stars Above, Earth Below, p. 426.

[22] Nordgren, Stars Above, Earth Below, pp. 424-426.

[23] Holbrook, ‘How Odd is Odd? Studying astronomers,’ p. 6.

[24] Holbrook, ‘How Odd is Odd? Studying astronomers,’ p. 6.

[25] Fabio Falchi et al, ‘The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness,’ Science Advances, 2 (6), American Association for the Advancement of Science, (2016), p. 1.

[26] Bogard, The End of Night, pp. 269-271.

[27] Blair, Sark in the Dark, p. 147.

[28] Nordgren, Stars Above, Earth Below, p. 426.

[29] Nordgren, Stars Above, Earth Below, p. 426.

[30] Louv, Last Child in the Woods, p. 157.

[31] Nicholas Campion, preface to Sark in the Dark: Wellbeing and Community on the Dark Sky Island of Sark, by Ada Blair (Ceredigion, Wales: Sophia Centre Press, 2016), p. xxvii.