by Jessica Heim

This paper explores the relationship between the sky and bodies of water in my home state of Minnesota, U.S.A. The aim of this research was to delve into the myriad ways in which the sky is reflected in the water and what it is like to be in this environment. Using a phenomenological approach, I regularly spent time by two bodies of water which I had a particular fondness for, recorded my observations, feelings and insights regularly during a three month summer period, and took many photographs of the water and sky. I then analyzed my findings in the context of literature discussing the value of this method of inquiry, that of immersing oneself in an experience of the sky and the natural world, giving particular attention to the writings of nineteenth century American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau. I found that experiencing the reflection of the sky on lakes and rivers, both during the day and at night, and in a variety of weather conditions, may allow one to not only feel a part of the environment in which one is immersed, but also to connect to past times, to those who have come before, and to the larger universe as well.

Introduction

The aim of this research is to explore the relationship between sky and bodies of water in my home state of Minnesota and to consider the reflection of aspects of sky to be found in water. By reflecting the light and colors of the sky, lakes and rivers make the heavens more tangible, pulling them down to earth. This research, approached from a phenomenological perspective, involves reflection upon my own personal responses to experiencing the sky and water in various times of day and night and under differing weather conditions.

Academic Rationale

In Walden, nineteenth century American transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau reflects upon the two years (1845-1847) he spent living in a cabin he built outside Concord near Walden Pond.[1] In this work, Thoreau writes extensively about his observations of nature and includes substantial commentary about his thoughts on Walden Pond and its reflections of its surroundings. Thus, in the tradition of Thoreau, my research aims to delve into the experiences, thoughts and reflections one may experience as a result of extended observation of sky and water.

Methodology

This research will utilize a phenomenological approach, as discussed by Christopher Tilley and Belden Lane.[2]It will draw upon my experiences with the sky and natural bodies of water in Minnesota, USA. The majority of my observations are of the Mississippi River and the sky as seen from my backyard in central Minnesota, though some are of a small lake by my grandma’s house in northern Minnesota. As part of this research, I have kept a sky journal, in which I have written my thoughts on observations of the sky and water from June through August 2017. In addition, to provide a visual reference to this journal and to more comprehensively capture my experience in the field, I have taken photographs of the sky and water throughout this period. I made prints of my favourite images, placed them in a specially designated photo album, and selected those most relevant to this essay to include here.

Reflexive Considerations

I am a Caucasian woman, and the location which I have spent the most time for this research is an area where I have lived for most of my life (about three decades). Watching the changing reflections of the sky upon the water in various times of day, weather, and seasons is not a new experience for me. For as long as I can remember, I have enjoyed watching the play of light upon the water. What is new to me for this research is the more structured aspect it has given this pastime – the heightened focus of regularly writing about my experiences with this environment and of more intense reflection on what these experiences mean to me.

Literature Review

Christopher Tilley has argued that a phenomenological approach is of much value in understanding the world and our relationship to it.[3] Phenomenology is, as Belden Lane describes, a way of interacting with the world in which one ‘listens to the place itself.’[4]As Tilley elaborates, with a phenomenological approach, ‘We experience and perceive the world because we live in that world and are intertwined within it. We are part of it, and it is part of us.’[5] Aspects of the world which are typically seen as inanimate, such as stones, are seen to essentially have a sense of agency, as they influence one’s consciousness. [6] Tim Ingold also utilizes a phenomenological perspective to consider the nature of the sky and human perception of it. He observes that without air’s transparent qualities, perception of sky, or anything at all, would be impossible.[7] He considers the difficulty of defining ‘sky,’ but suggests, ‘the sky is the kingdom of light, sound, and air.’[8] Thus our perception of sky is influenced by the light we see, the sounds we hear, and the movement of air we feel.

Though Thoreau does not make use of terminology such as ‘phenomenology,’ he clearly values the importance of regularly being out in the world and experiencing it first hand – obtaining knowledge from books alone is not sufficient.[9] As he observes, ‘What is a course of history or philosophy . . . or the best society . . . compared with the discipline of looking always at what is to be seen?’[10] Thoreau explains why he went to live at Walden Pond. He says, ‘I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately . . . and not, when I came time to die, discover that I had not lived . . . I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.’[11] In the course of ‘living deep,’ Thoreau makes extensive observations of the natural world around him and reflects on the significance of what he sees and experiences.

Similarly, astronomy enthusiast Fred Schaaf points out the importance of naked eye observation of the sky. He notes, ‘the best way to learn them [the many features visible in the sky] is though your own personal, intimate discoveries of them. In the most ultimate sense, there is no true replacement for direct observation in astronomy.’[12] Like Thoreau, Schaaf makes the argument that direct personal experience with the world is essential for better understanding and appreciation of it.

Field Work and Discussion

Undertaking phenomenological research on the combination of water and sky in Minnesota seemed very appropriate. The name, ‘Minnesota’ is derived from the Dakota Mni Sota Makoce, translated as ‘sky-tinted water’ or ‘the land where the waters are so clear they reflect the clouds.’[13] The state’s nickname is ‘Land of 10,000 Lakes’ (there are actually 11,842) and the state motto is l’etoile du nord (star of the north).[14] Given the ubiquitous presence of lakes, rivers and streams in the state, experiencing where the water meets the sky seemed like the perfect way to immerse oneself in a Minnesotan experience of sky.

A few points to note – first, I live on the west bank of the north-south flowing Mississippi River. Thus when I face the river, I face east. The same is true for my grandma’s house – the sun and moon appear to rise above the lake. Also, area where I live is near a bend in the river where the river is unusually wide compared to its width just a few miles to the north or south. Due to this, the opposite shore is quite distant, and it consequently, aside from the current, has more of the feel of being on a lake. In addition, I live several miles north of a medium sized city, thus for most of my life, the light pollution affecting the view of the sky at night was restricted to the southern part of the sky. My grandma lives in a very small town much further from larger population centers, hence, at her house, the sky is darker at night and is significantly less affected by light pollution.

Reflection, Light, and Perception

A central theme which repeatedly came up throughout this research was the idea of reflection. The water acts as a mirror which it reflects what is going on above it. As Thoreau muses, ‘Walden is the perfect forest mirror . . . Sky water.’[15] When the skies are blue, the Mississippi is a rich hue of marine blue (Fig. 4). During stormy weather, the water turns slate grey, even darker than the storm clouds above it (Fig. 5), and it is a wonderful reflector of the light of the rising sun and moon (Fig. 6). One morning, I photographed the rising sun, and the sun’s image reflected in the water was blazingly bright! (Fig. 7) I thought of this experience when I read Thoreau’s comment about watching the sun set above Walden Pond. He notes, ‘you are obliged to employ both your hands to defend your eyes against the reflected as well as the true sun.’[16] Similarly, the purples and pinks visible in the eastern sky at sunset are reflected upon the water (Fig. 8). As Thoreau observes, water is ‘continually receiving new life from above,’ as it reflects the quality and appearance of the air and sky which it lies beneath.[17]

As beautiful as all these scenes are, the one that I found myself writing about with the most excitement was the sight of the light of the morning sun, once it has gained sufficient elevation, bouncing off the gently flowing water. As I wrote on the morning of 5 June, ‘The light sparkling on the water is so beautiful, so magical… One cannot begin the day in a better way (Figs. 6 & 7).’ Thoreau too, makes note of the play of light upon the water, noting, ‘White Pond and Walden are great crystals on the surface of the earth, Lakes of Light.’[18] To me, the light of the rising sun or moon makes the river appear as if it is covered in thousands of sparkling diamonds. This is made possible not only by the light of the celestial body, but also by the combination of a light breeze and slight current, which causes the water to move and thus the light to sparkle. Consequently, the air and sky are both acting upon the water which in turn reflects back these stimuli to the observer. Thus is it is not only that the environment and observer can act upon each other, or as Tilley describes, ‘I touch the stone and the stone touches me,’ but also that different parts of the environment interact with one another.

In addition, while I admired the light sparkling, reflecting off the water that morning, I realized that was not all that was sparkling. I ‘noticed how the play of light was appearing not only on the water, but on the leaves of the huge cottonwood tree in our backyard. It looked like there were diamonds in the water as well as the tree.’[19] This cottonwood tree is a tremendous presence in my backyard and its leaves rustle in the slightest breeze. I reflected further on cottonwood trees, noting, ‘It’s like they are connected to the sky in several ways – their leaves reflect the light of the sun, the wind makes this light move and sparkle (Fig. 8).’[20]The wind blowing the leaves not only results in a beautiful display of light, but of sound as well. As I described, ‘I’ve always loved the sound of cottonwood leaves rustling in the wind. My dad (who passed away when I was in my early twenties) did too. He often commented on how he loved to hear the sound of the wind rustling the leaves of these trees. So when I hear this sound, fond memories of my dad always come to mind.’[21] In describing the ideas of musicologist Victor Zuckerkandl, Ingold makes an observation quite pertinent to this scene, ‘in opening our eyes and ears to the sky, vision and hearing effectively become one. And they merge with feeling, too, as we bare ourselves to the wind.’[22] This perfectly describes my experience observing the sky, river, and environs. As I wrote shortly after a description of the interaction of light and wind upon the water and the cottonwood tree, ‘Though I feel differently depending on the weather and time of day, one thing is consistent, the river makes me feel. I always feel more alive by it.’[23] Thus in being immersed in ‘the kingdom of light, sound, and air’ – seeing the light upon the water, hearing the leaves in the wind, and feeling the breeze against my skin – in feeling these physically in my body, I feel, too, in the emotional sense of the word.[24]

Time

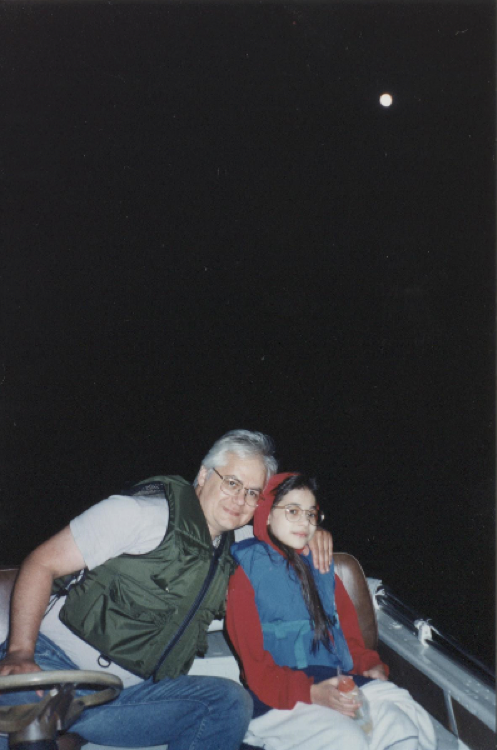

Another theme which repeatedly surfaced in my reflections on my experience with the water and sky, was that of time and its connection to place. Particularly when observing the sky from my backyard and reflecting upon how I felt about it, I found that many memories of that same place from my childhood came to mind. As Alexandra Harris observes in her book about weather in the lives and works of English writers and artists, ‘Our weather is made up of personal memories and moods: an evening sky is full of other evenings.’[25] During this research, I frequently recalled time spent on or near the river with my dad (Fig. 9). As I recalled, ‘We would sometimes boat up the river at night, to better enjoy the moonlight on the water (Fig. 10).’[26] Reflecting on watching the river in the morning, I noted, ‘When I am looking at the morning light dancing as sparkles across the water, I could just as easily be five years old. It feels much the same to be with the sky, trees, and water as it did then.’[27] Thoreau similarly remarks upon such timelessness of a place, ‘Why, here is Walden, the same woodland lake that I discovered so many years ago; . . . it is the same liquid joy and happiness.’[28] As he goes on to describe, ‘I see by its face that it is visited by the same reflection; and I can almost say, Walden, is it you?’[29] Thus, by being immersed in a landscape which appears relatively constant over the years, one can, in a way, connect back to a past time.

Photo: Sister Orlean Pereda.

Photo: Sister Orlean Pereda.

The idea of connecting to other times via sky observation also came up in another way during this research. When I observed the sky at night from the end of the dock (Fig. 11 – photograph taken during the day, since those I took at night did not turn out well]) at my grandma’s house, the sky was quite dark, many faint stars were easily visible, and the Milky Way stretched as a gigantic arch above me, from Sagittarius on the southern horizon, through Cygnus overhead, to Cassiopeia in the north. As I laid on my back at the end of the long dock, essentially surrounded by the water around and beneath me and by the starry expanse above me, I pondered the idea that, even more than a lake or river, the view of the night sky can be seen as a relatively unchanging place. As I wrote that night, ‘Sky is a primary source, which, when experienced as truly dark, can be experienced very similarly to how ancient people saw it. A way of connecting to the past and transcending time.’[30] Clive Ruggles, in a discussion about striving to comprehend they way past peoples viewed the world around them and their place in it, notes the value of the sky in this endeavour, as, ‘unlike the rest of their perceived world, the sky is a part that we can visualize directly.’[31] Thus by immersing oneself into a night-time environment such as this, one can connect more closely with the earth and sky as it was experienced long ago.

Darkness

When thinking about all the experiences I had with the sky, river, and lake at night this summer, the importance of darkness came to mind. For darkness at night is essential in order to continue to experience the wonder of the night sky, and in so doing, to feel a sense of connection to both those that have come before us and to the universe itself. As Tyler Nordgren points out, when we lose the night sky, ‘we lose our place in the Universe’ and ‘a direct visible connection to our ancestors . . . In short, we lose a tangible link to ourselves that gives life meaning beyond the here and now.’[32]In my journal, I reflected upon the loss of the night sky, recalling memories of ‘Sitting on the dock with my dad – looking at the river as it grew dark. . . I remember my dad telling me how when he and my mom had first moved here, the only light visible on the opposite shore of the river was a little green light . . . I would always ask him to point out that light to me. As time went on, more lights appeared, and he was no longer able to make out that light.’[33] As frustrating as that was, it was relatively minor compared to the recent influx of bright white LEDs which are much more effective at obliterating the view of the stars. Though the daytime view of the sky and the Mississippi remains much the same as in years past, the night-time version has changed substantially, and it is no longer possible to see the stars reflected in the waters below. In not being able to experience a dark, starry sky, I have lost the ability (unless I drive a considerable distance to a remote area) to directly experience the night-time sky in the same way – it’s akin to trying to experience what a forest is like after most of the trees have been cut down, the animals have left, and the understory plants have been trampled. Thoreau wrote in his journal, ‘I should not like to think that some demigod had come before me and picked out some of the best of the stars. I wish to know an entire heaven and an entire earth.’[34] In my own sky journal, I found myself repeatedly expressing my frustration with the rapidly declining accessibility of the night sky and lamenting that if current trends continue, future generations will not ‘know an entire heaven.’ As astro-photographer Dietmar Hager argues, if people cannot see the stars, they will ‘have no relationship with the sky.’[35] Consequently, something which has been a fundamental part of humans’ experience on earth, their connection to the larger cosmos, will have been lost.

Final Thoughts

Though distinct themes can be found in my sky journal, I found that when immersed in the ‘weather-world,’ as Tilley terms it, all the diverse qualities of the elements around me are intertwined and inseparable.[36] When I see the light of the sun or moon reflected on the water, I simultaneously feel the touch of the wind and note its effects on all that I see. At the same time, I can hear the water lapping at the shore and the call of a bird soaring overhead. Thus Tilley’s understanding of sky as ‘the kingdom of light, sound, and air,’ perfectly encompasses the entirety of my experiences in this environment.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to explore the intersection of water and sky using a phenomenological approach. The first theme discussed was how the water’s reflection of the sky changes markedly based on time of day and weather, as well as how light and the movement of air affects not only the appearance of water, but the trees at its bank and an individual immersed in this environment. The idea of place and its relationship to time was also explored. As Tilley observes, memories are an integral part of one’s experience and being in a place routinely can be seen as a series of ‘biographic encounters.’[37] In addition, I found that viewing a dark, starry sky can serve as a means to connect one to both those who have come before and to the larger cosmos. The continued existence of dark night skies is essential in order to maintain this connection. In conclusion, to understand all facets of the relationship between sky and water, they must be able to be experienced in all conditions – in both stormy weather and fair, in both the brightness of the noontime sun and in night so dark that the stars and the Milky Way can be seen in the sky above and in the waters below.

Bibliography

Explore Minnesota Tourism, Five Ways to Enjoy Minnesota’s 10,000 Lakes,< http://www.exploreminnesota.com/travel-ideas/five-ways-to-enjoy-minnesotas-10000-lakes/> [accessed 13 August 2017].

Hager, Dietmar, ‘Ethical Implications of Astrophotography and Stargazing,’ in The Imagined Sky: Cultural Perspectives,ed. by Darrelyn Gunzburg, pp. 305-318 (Bristol, Connecticut: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016).

Harris, Alexandra, Weatherland: Writers & Artists Under English Skies (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2015).

Heim, Jessica, Sky Journal, June – August 2017.

Ingold, Tim, ‘Earth Sky, Wind, and Weather,’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13(2007), 19-38.

Ingold, Tim, ‘Reach for the Stars! Light, Vision, and the Atmosphere,’ in The Imagined Sky: Cultural Perspectives,ed. by Darrelyn Gunzburg, pp. 215-233 (Bristol, Connecticut: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016).

Lane, Belden C., Landscapes of the Sacred: Geography and Narrative in American Spirituality, Expanded edn (Baltimore, MD and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).

Nordgren, Tyler, Stars Above, Earth Below: A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks(Chichester, UK: Praxis, 2010).

Ruggles, Clive, Ancient Astronomy: An Encyclopedia of Cosmology and Myth, (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc, 2005).

Schaaf, Fred, The Starry Room: Naked Eye Astronomy in the Intimate Universe (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1988).

State of Minnesota, State Motto,< https://mn.gov/portal/about-minnesota/state-symbols/flag.jsp> [accessed 13 August 2017].

Thoreau, Henry David, Journal, in The Journal: 1837-1861 by Henry David Thoreau, ed. by Damion Searls, Preface by John R. Stilgoe (New York: New York Review of Books, 2009).

Thoreau, Henry David, Walden,in Walden and Civil Disobedience, Introduction and Notes by Andrew S. Trees, (New York: Barnes & Noble: 2012), pp. 1- 258.

Tilley, Christopher, A Phenomenology of Landscape(Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1994).

Tilley, Christopher, The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology(Oxford: Berg, 2004).

Upham, Warren, Minnesota Place Names: a Geographical Encyclopedia,3rd edn (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001).

Westerman , Gwen and Bruce White, Mni Sota Makoce: the Land of the Dakota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012).

[1]Henry David Thoreau, Walden,in Walden and Civil Disobedience, Introduction and Notes by Andrew S. Trees (New York: Barnes & Noble: 2012), pp. 1- 258.

[2]Christopher Tilley , The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology(Oxford: Berg, 2004); Belden C. Lane, Landscapes of the Sacred: Geography and Narrative in American Spirituality, Expanded edition (Baltimore, MD and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), p. 26.

[3]Tilley, The Materiality of Stone, p.31.

[4]Lane, Landscapes of the Sacred, p. 44.

[5]Tilley, The Materiality of Stone, p. 2.

[6]Tilley, The Materiality of Stone, p. 16.

[7]Tim Ingold, ‘Reach for the Stars! Light, Vision, and the Atmosphere,’ in The Imagined Sky: Cultural Perspectives, ed. by Darrelyn Gunzburg (Bristol, Connecticut: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016), p. 225.

[8]Ingold, ‘Reach for the Stars!’ p. 231.

[9] Thoreau, Walden, p. 86.

[10]Thoreau, Walden, p. 86.

[11]Thoreau, Walden, p. 20.

[12]Fred Schaaf, The Starry Room: Naked Eye Astronomy in the Intimate Universe (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1988), p. 2.

[13]Warren Upham, Minnesota Place Names: a Geographical Encyclopedia,3rd edn (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001), p. 4; Gwen Westerman and Bruce White, Mni Sota Makoce: the Land of the Dakota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012), p. 13.

[14]Explore Minnesota Tourism, Five Ways to Enjoy Minnesota’s 10,000 Lakes,<http://www.exploreminnesota.com/travel-ideas/five-ways-to-enjoy-minnesotas-10000-lakes/> [accessed 13 August 2017]; State of Minnesota, State Motto,< https://mn.gov/portal/about-minnesota/state-symbols/flag.jsp> [accessed 13 August 2017].

[15]Thoreau, Walden, p. 147.

[16]Thoreau, Walden, p. 145.

[17]Thoreau, Walden, p. 147.

[18]Thoreau, Walden, p.155.

[19]Jessica Heim, Sky Journal, June – August 2017, 5 June journal entry.

[20]Heim, Sky Journal, 10 June journal entry.

[21]Heim, Sky Journal, 5 June journal entry.

[22]Ingold, ‘Reach for the Stars!’ p. 231.

[23]Heim, Sky Journal, 5 June journal entry.

[24]Ingold, ‘Reach for the Stars!’ p. 231.

[25]Alexandra Harris, Weatherland: Writers & Artists Under English Skies (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2015), p. 13.

[26]Heim, Sky Journal, 15July journal entry.

[27]Heim, Sky Journal,5 June journal entry.

[28]Thoreau, Walden, p. 150.

[29]Thoreau, Walden, p. 150.

[30]Heim, Sky Journal,24 July journal entry.

[31]Clive Ruggles, Ancient Astronomy: An Encyclopedia of Cosmology and Myth, (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc, 2005), p. xi.

[32]Tyler Nordgren, Stars Above, Earth Below: A Guide to Astronomy in the National Parks(Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing, 2010), p. 428.

[33]Heim, Sky Journal,15 July journal entry.

[34]Henry David Thoreau, The Journal: 1837-1861 by Henry David Thoreau, ed. by Damion Searls, Preface by John R. Stilgoe (New York: New York Review of Books, 2009), entry from March 23, 1856, p. 373.

[35]Dietmar Hager, ‘Ethical Implications of Astrophotography and Stargazing,’ in The Imagined Sky: Cultural Perspectives,ed. by Darrelyn Gunzburg, pp. 305-318 (Bristol, Connecticut: Equinox Publishing Ltd., 2016), p. 307.

[36] Tim Ingold, ‘Earth Sky, Wind, and Weather,’ The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 13(2007), 19-38.

[37] Christopher Tilley, A Phenomenology of Landscape(Oxford: Berg Publishers, 1994), p. 27.