Chris Layser

This paper presents a brief comparative analysis of two important depictions of the sky from the corpus of Maya art and iconography: the so-called ‘Maya Zodiac’ found within the pages of the Paris Codex and the painted murals of Room 2 at Bonampak in Chiapas, Mexico. This comparison will focus on three iconographical elements relating to the Maya sky: the skyband, the turtle, and the peccary — the latter of which is now effaced in the Paris Codex — in order to establish whether they represent three important sky markers relating to the Maya creation myth.

Although the exact age and provenience of the Paris Codex, a Maya screen-fold hieroglyphic manuscript, is unknown, Bruce Love suggests ‘the best working hypothesis’ is that it was produced in the Post-Classic Yucatec polity Mayapan, ‘near the end of that city’s existence as a power centre, around A.D. 1450’.[1]Gregory Severin presents it as an astronomical ephemeris, demonstrating that pages 23-24 represent a thirteen-constellation zodiac which the Maya used in order ‘to calculate the sidereal year’.[2]These pages are frequently referred to as the ‘Maya Zodiac’, although Love suggests a ‘dominant constellation’ model may be more accurate, arguing that though ‘stars and groupings of stars were extremely potent forces, and yearly movements of the constellations held great meaning… these stars did not have to lie within the [18˚ wide] zodiacal band..[3]This analysis will refer to the constellations as zodiacal and will compare two of them to animal figures within cartouches painted onto the corbelled ceiling of Bonampak Room 2.

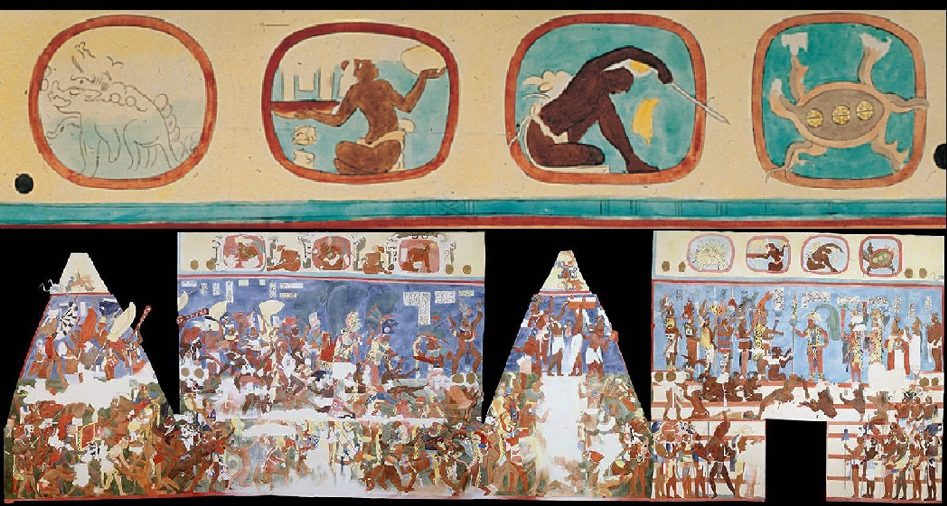

The murals were painted in the three rooms of Structure 1 and ‘work as a unit formally and iconographically’ to tell a story set near the end of the Classic period.[4]The Room 2 mural depicts a battle on one wall and a victory celebration on the other — set beneath what appears to be a starry sky. Harvey and Victoria Bricker describe this ‘one small portion of the murals’ as ‘relevant to any investigation of a pre-Columbian Maya zodiac’.[5]Unfortunately, as Michael Coe explains, Maya scholarship is now ‘dependent upon copyists for the analysis of the Bonampak murals’, for though the paintings were ‘relatively intact upon their discovery in 1946, [they] are now only shadows of their former selves.’[6]

The Skybands

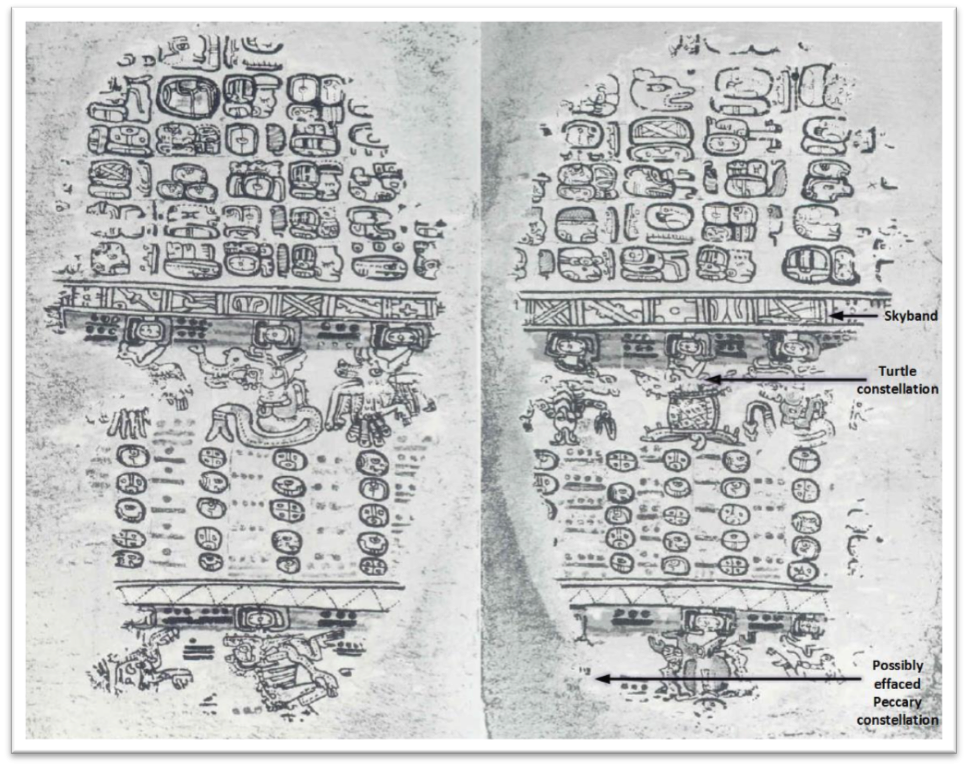

An important and ever-present aspect of Maya celestial iconography is the skyband, identified in Figure 1. Animal images hang from the dominant skyband of the Maya Zodiac, which bisects the two pages, while a less ornate skyband crosses the bottom of the pages. Beth Collea’s early 1980s study sets the following three criteria for their identification: at least one of a set of specific glyphs is represented, the glyphs are shown ‘fused together rather than in separate cartouches’, and no affixes appear within the glyphs in the band.[7]The skyband glyphs on the upper-register of the Maya Zodiac reads from right to left and contains a variety of glyphs pertaining to the sky, heavenly bodies, or signs of the night.[8]The band on the lower register has no diagnostics, only a zig-zag dotted line, which may represent a serpent’s pattern and out of context would likely not pass Collea’s identification criteria as a skyband at all.

Herbert Spinden first pointed out that though the skyband ‘turned downward at the left’ and ‘cut off short at the right end’ it must represent ‘the elongated body of a Two-headed Dragon.’[9]John Carlson and Linda Landisbelieve the skyband ‘in all its functional representations is the body of the bicephalic dragon’ which becomes the ‘cosmic border framing the Maya world’.[10]Linda Schele realized the ‘Double-Headed Serpent’ which was draped around and through the branches of the ‘World Tree’ of the Milky Way in so much Maya iconography specifically represented the ecliptic- the ‘line of constellations in which the sun rises and sets throughout the year’.[11]It is now well understood that skybands point to celestial activity, and these bands bear import roles in the astronomical interpretation of both the Paris Zodiac and the murals of Bonampak.

Subtle and subdued in comparison to the upper skyband in the Paris Codex zodiac pages, the blue-green skyband of Room 2 at Bonampak separates the ‘battle scene’ of the south-west wall and the ‘victory scene’ of the north-east wall from the celestial happeningson the corbelled ceilings above (Figure 2). Mary Ellen Miller thought that the front head of this bicephalic monster was identifiable atop the east wall of Room 1.[12]Although the crossbands glyph – which Schele suggests represents the intersection of the ecliptic and the Milky Way — can be determined, no other glyphs are discernible.[13]Bricker and Bricker suggest that:

The painting was never completed… the sky band in its present form appears to have ten rectangular fields or segments. Both the leftmost and the rightmost two segments contain cross-bands signs similar to those [at] Las Monjas at Chichén Itzá… [while] the central six segments… are empty.’[14]

Taking account of the attention to detail in the rest of the mural, Bricker and Brickers’ opinion seems unlikely, and the lack of detail may be a stylistic choice of the artist. The real purpose of the skyband, Miller contends, is ‘dividing human space and heavenly space’.[15]Here the cartouches set atop of the skyband — as opposed to the Paris Codex where figures hang below. This identifies them as heavenly images, and informs, as do all representations of the two-headed serpent, of observation along the ecliptic.

The Turtle

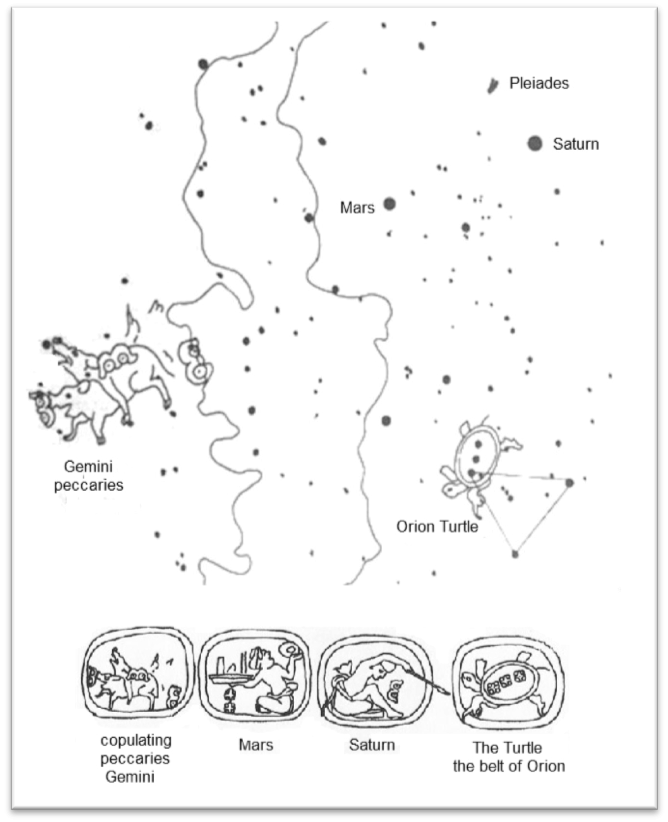

Of the recognisable figures hanging from the skybands of the Paris Zodiac, only the turtle is found on the Bonampak murals; and from the frequency of the turtle’s depiction throughout Maya art, its importance becomes apparent (Figure 3). Severin notes the sixteenth-century Spanish/Maya dictionary Calepino de Mortul‘lists but two Maya constellations with their known counterparts in the Greco-Babylonian zodiac: tzab, the ‘tail of the rattlesnake’ known to us as the Pleiades…and ac ek, the “turtle stars”’, which corresponded in part to the stars in the constellation Gemini or Orion.[16]The Maya creation story as recorded on stele from Quiriguá explains how three ‘hearthstones’ were placed in the sky at the beginning of the current age.[17]Dennis Tedlock found ‘the stars Alnitak, Saiph, and Rigel in Orion… are said by the Quichés to be the three hearthstones of the typical Maya kitchen fireplace arranged to form a triangle’ and that these stars ‘enclose the Orion Nebula … said to be a smoky fire’.[18]The turtle which sits upon the skyband at Bonampak has three star symbols upon its back, and the preponderance of evidence suggests this represents the Belt of Orion.

The Peccary

A second cartouche on the Bonampak ceiling contains copulating peccaries, yet the peccary is not found in the Paris Zodiac. Floyd Lounsbury compared these pages to ‘a band of astral or zodiacal signs inscribed on the Casa de las Monjas at Chichen Itza’ which ‘gives evidence for a “peccary” … with both the turtle and the peccary depicted over “star” signs within their respective cartouches’.[19]The question could be asked whether these various sources contain the same collection of celestial images. Bernadette Brady has demonstrated that in the Western tradition the ‘images that humanity has placed in the sky’ display a ‘persistence through time’ changing little over the span of millennia.[20]It is reasonable, therefore, to suggest that the Maya constellations had remained static over the course of mere centuries, and that the peccary constellation would have its place within the Paris Codex zodiac pages. Bricker and Bricker pointed to the empty space at the bottom-left corner of page 24 and ‘suggested that the peccary… might fit into the sequence at this position… However, this suggestion was based solely on [their] interpretation of murals on the north wall of Room 2 at the Classic site of Bonampak.’[21]Analysis of the embedded arithmetic by Richard Johnson and Michel Quenon suggests this spot would be home to the stars that comprised the constellation of Gemini.[22]

Lounsbury interpreted date of the battle depicted on the mural from the heavily effaced glyphs to be 13 Chichan 13 Yax (9.18.1.15.5).[23]Linda Schele later used this date, correlating to 6 August 792 CE, to show that ‘in the hours before dawn the constellations of Gemini and Orion had hovered above the eastern horizon’ and made the connection that ‘Gemini had to be the copulating peccaries’.[24]She noted this date was only four days before the creation date of 13 August and suggested these two constellations at the intersection of the ‘World Tree’ and the ‘Double-Headed Dragon’ marked the location in the sky where the act of creation took place (Figure 4). Further evidence in support of this conclusion is presented in Figure 3 which includes images of the Maize God reborn at the moment of creation, emerging from a crack in the back of both a turtle and a peccary.

In conclusion, this paper presented a comparative analysis of pages 23-24 of the Paris Codex- which demonstrates the Maya recognised thirteen constellations along or near the ecliptic, and murals painted upon the walls of Room 2, Structure 1 at Bonampak. Both display a skyband representing the ‘Two-headed Dragon’ of the ecliptic, though the skyband of the Paris Codex offers complex glyphic diagnostics whereas the skyband of the murals is in its most simplistic form. Two constellations were considered: the turtle and peccary. The turtle is present in both the codex and the murals and has been identified as the stars of Orion by ethno-astronomical investigations. It has been argued that the peccary, which is present on the mural, once existed on the codex as well and represents the stars comprising the constellation Gemini. Furthermore, it has been suggested that these two constellations were important sky markers pertaining to the Maya story of creation. When the ancient Maya looked to the pre-dawn summer sky, the turtle and the peccary were important figures perceived at this intersection of the ecliptic and Milky way.

Bibliography

Bernadette Brady, ‘Images in the Heavens: A Cultural Landscape’, in The Imagined Sky, ed. by Darrelyn Gunzburg, (Sheffield and Bristol: Equinox Publishing, 2016).

Harvey M. Bricker and Victoria R. Bricker, ‘Zodiacal References in the Maya Codices’, in The Sky in Mayan Literature, ed. by Anthony Aveni, (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

Harvey M. Bricker and Victoria R. Bricker, Astronomy in the Maya Codices, (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2011).

John B Carlson and Linda C. Landis, ‘Bands, Bicephalic Dragons, and Other Beasts: The Skyband in Maya Art and Iconography’ in Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, ed. by Merle Greene Robertson and Elizabeth P. Benson, (San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985).

Michael D. Coe, ‘Art and Illusion among the Classic Maya’, Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol. 64 (2005).

Michael D. Coe, The Maya Scribe and His World, (New York: The Grolier Club, 1973).

Beth A. Collea, ‘The Celestial Bands in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing’, in Archaeoastronomy in the Americas, ed. Ray A. Williamson, (Los Altos and College Park: Ballena Press and The Center for Archaeoastronomy, 1981).

Martha Ilia Nájera Coronado, Bonampak, (Nápoles, Mexico: Gobierno del Estado de Chiapas, 1991).

David Freidel, Linda Schele and Joy Parker, Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman’s Path, (New York, London, Toronto and Sydney: William Morrow Paperbacks, 1993).

Floyd G. Lounsbury, ‘Astronomical Knowledge and its Use at Bonampak, Mexico’ in Foundations of New World Cultural Astronomy, ed. Anthony Aveni (Boulder: University of Colorado, 2008). Originally published in Archaeoastronomy in the New World, ed. Anthony Aveni, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982).

Bruce Love, The Paris Codex: Handbook for a Maya Priest, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994).

Mary Ellen Miller, The Murals of Bonampak, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986).

Mary Ellen Miller and Claudia Brittenham, The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court: Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013).

Gregory M Severin, ‘The Paris Codex: Decoding an Astronomical Ephemeris’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 71, No. 5 (1981).

Herbert J. Spinden, ‘The Question of the Zodiac in America’, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1916).

Dennis Tedlock,Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of The Mayan Book of The Dawn of Life and The Glories of Gods and Kings, (New York: Touchstone, 1996).

Dennis Tedlock, 2000 Years of Mayan Literature, (Berkley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2010).Khistaan D. Villela and Linda Schele, ‘Astronomy and the Iconography of Creation Among the Classic and Colonial Period Maya’ In Eighth Palenque Round Table, 1993, eds. Merle Greene Robertson, Martha J. Macri and Jan McHargue, (Aust

[1]Bruce Love, The Paris Codex: Handbook for a Maya Priest, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994), p.13.

[2]Gregory M. Severin, ‘The Paris Codex: Decoding an Astronomical Ephemeris’, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 71, No. 5 (1981), p. 37.

[3]Love, The Paris Codex, p. 89.

[4]Mary Ellen Miller, The Murals of Bonampak, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), p.23

[5]Harvey M. Bricker and Victoria R. Bricker, ‘Zodiacal References in the Maya Codices’, in The Sky in Mayan Literature, ed. by Anthony Aveni, (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 176.

[6]Michael Coe, ‘Art and Illusion among the Classic Maya’, Record of the Art Museum, Princeton University, Vol. 64 (2005), p. 55.

[7]Beth A. Collea, ‘The Celestial Bands in Maya Hieroglyphic Writing’, in Archaeoastronomy in the Americas, ed. Ray A. Williamson, (Los Altos and College Park: Ballena Press and The Center for Archaeoastronomy, 1981), p. 215.

[8]Carlson and Landis, ‘The Skyband in Maya Art’, pp. 135-138.

[9]Herbert J. Spinden, ‘The Question of the Zodiac in America’, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 18, No. 1 (1916), pp. 74-75.

[10]John B. Carlson and Linda C. Landis, ‘Bands, Bicephalic Dragons, and Other Beasts: The Skyband in Maya Art and Iconography’, in Fourth Palenque Round Table, 1980, ed. by Merle Greene Robertson and Elizabeth P. Benson, (San Francisco: The Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1985), p.115

[11]David Freidel, Linda Schele and Joy Parker, Maya Cosmos: Three Thousand Years on the Shaman’s Path, (New York, London, Toronto and Sydney: William Morrow Paperbacks, 1993), pp. 78-79.

[12]Miller, The Murals of Bonampak,p. 93.

[13]Freidel, Schele and Parker, Maya Cosmos,pp. 75-87.

[14]Bricker and Bricker, ‘Zodiacal References in the Maya Codices’, p. 177.

[15]Mary Ellen Miller and Claudia Brittenham, The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court: Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak, (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2013), p. 105.

[16]Severin, ‘The Paris Codex: Decoding an Astronomical Ephemeris’, p. 8.

[17]Dennis Tedlock, 2000 Years of Mayan Literature, (Berkley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 2010), pp. 43-58.

[18]Dennis Tedlock, Popol Vuh: The Definitive Edition of The Mayan Book of The Dawn of Life and The Glories of Gods and Kings, (New York: Touchstone, 1996), p. 236.

[19]Floyd G. Lounsbury, ‘Astronomical Knowledge and its Use at Bonampak, Mexico’, in Foundations of New World Cultural Astronomy, ed. by Anthony Aveni (Boulder: University of Colorado, 2008), p.570

[20]Bernadette Brady, ‘Images in the Heavens: A Cultural Landscape’, inThe Imagined Sky, ed. Darrelyn Gunzburg, (Sheffield and Bristol: Equinox Publishing, 2016), p. 235.

[21]Harvey M. Bricker and Victoria R. Bricker, Astronomy in the Maya Codices, (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2011), p. 706.

[22]Khistaan D. Villela and Linda Schele, ‘Astronomy and the Iconography of Creation Among the Classic and Colonial Period Maya’ In Eighth Palenque Round Table, 1993, ed. by Merle Greene Robertson, Martha J. Macri and Jan McHargue. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), p. 4.

[23]Lounsbury, ‘Astronomical Knowledge and its Use at Bonampak’, pp. 582-583.

[24]Freidel, Schele and Parker, Maya Cosmos, p. 80.