by Christopher Layser

This qualitative investigation into contemporary cosmology utilized an online questionnaire and semi-structured participant interviews with a targeted group of twenty respondents in the American Northeast as its primary methodology in exploring factors contributing to the development of personal cosmologies. Cultural factors such as religious and secular education plus the influence family, friends and society- whether positive or negative- proved paramount in the formation of worldviews. Informants with varying religious, scientific, and philosophical engagement to the subject matter applied their respective methodologies in conveying beliefs as to the origin of the cosmos, ranging from creation narratives to emerging theories based upon observational astrophysics. The question of astrology and its application were posed, and the topics of cosmophobia and cosmophilia were introduced in order to explore the target group’s general perception of the Universe and their opinion of humankind’s place within it.

Introduction

The aim of this research is to explore the personal cosmologies of a small group of participants in the American Northeast using qualitative methods of data gathering. Through semi-structured interviews and questionnaire data, this investigation into deeply held beliefs and the comparative cosmologies of the informants will attempt to reveal important insight as to how and perhaps why individuals perceive the cosmos in the ways in which they do. Themes explored in this project include the factors contributing to the development of these personal cosmologies, narratives concerning the origin of the cosmos, beliefs surrounding the application of astrology, perceptions as to the nature of the universe and the importance of humankind’s place within it.

In modern discourse the term cosmology has come to describe two very distinct yet related disciplines. The first finds its home in astrophysics and is defined by Norris S. Hetherington as ‘the science, theory or study of the universe as an orderly system and the laws that govern it; in particular, a branch of astronomy that deals with the structure and evolution of the universe.’[1] The second finds its home in the humanities. Nicholas Campion considers this second use of the term as a ‘meaning system’ which ‘deals with mythic narratives, ways of seeing the sky, and the manner in which human beings locate themselves in space and time’.[2] Yet John North demonstrates how theses disciplines converge when he notes that ‘throughout the long history of theorizing about the universe…there have always been considerations of simplicity, harmony, and aesthetics, often masquerading under the name philosophy, and often directed by strongly held religious beliefs’ and thus ‘we cannot discount the place of the human psyche in modern cosmology.’[3]. Freya Mathews contends that these ‘cosmologies are not of course pulled out of the air to suit the convenience of the communities to which they are attached…they are conditioned by many and various historical, environmental, technological, psychological and social factors.’[4] This rationale can serve to focus the discussion of cosmology down to a very personal level, whereby the choices and beliefs to which one adheres begin to develop into one’s own personal cosmology.

Methodology

The target group of this research does not define any particular cohesive community other than it represents a sample of friends, family, co-workers, and acquaintances of the researcher, with additional individuals invited to participate based upon their professional engagement with the subject matter. The participants reside in various locales of the American Northeast- including parts of Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, New York, Massachusetts and Maryland. They ranged from thirty-one to seventy-six years of age with seventy percent identifying as male and thirty percent as female.[5] My own position in field could be defined as varying degrees of insider status: I am a white male; my age is nearly the mean of the target group; my religious affiliation is Christian and I am closely acquainted with much of the target group.

All participants were asked to engage in an online Google Forms questionnaire. The questionnaire introduction addressed ethical considerations informing participants that all data would be collected anonymously, remaining so until its destruction after the completion of this project. Twenty individuals completed the survey, although not all respondents answered all questions. Eltica de Jager Meezenbroek and colleagues suggest that ‘a questionnaire that transcends specific beliefs is a prerequisite for quantifying the importance of spirituality among people who adhere to a religion or none at all.’[6] Furthermore, Judith Bell writes that a well-designed questionnaire ‘will give you the information that you need, will be acceptable to respondents, and will give no problems during the analysis and interpretation phase.’[7] This questionnaire attempted work within these guidelines, posing carefully crafted questions intent on exploring beliefs concerning the origin and the nature of the cosmos.

In addition, five informants, chosen for their professional or religious engagement with the subject matter, were asked to participate in semi-structured interviews to gain deeper insight not attainable from a questionnaire. These five informants are referenced in this paper as the astronomer, the astrologer, the pastor, the Buddhist, and the psychologist. The interviews were conducted in person, with one exception, and were recorded with the explicit consent of the interviewee for later transcription. Monique Hennick, Inge Hutter, and Ajay Bailey suggest using interviews as a methodology aids in seeking ‘information on individual, personal experiences from people about a specific issue or topic’[8].

Influences on the Development of Personal Cosmologies

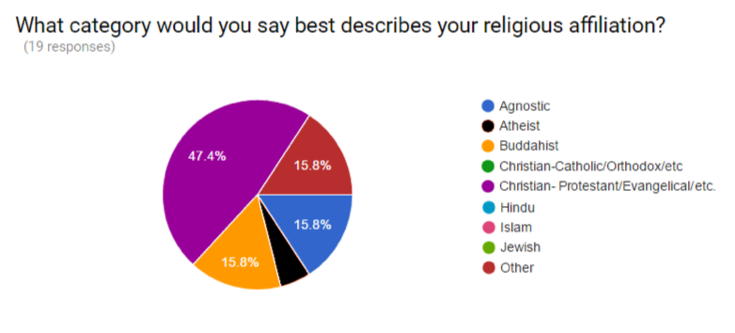

In the past, cosmology has ‘been closely intertwined with religious belief,’ explains Ernan McMullin, and ‘only within the last half-century or so has a specialized science of cosmology developed that makes no mention of God.’[9] In this study, when asked if they believed in God, twelve respondents answered yes.[10] When asked if they hold similar religious beliefs to one or both of their parents, eleven answered yes.[11] Nine identify as Protestant/Evangelical Christians.[12] It can be surmised from analysis of this data that many respondents adhere to a belief in God that had been conditioned from a familial ‘Christian’ culture in their formative years. The breakdown of religious affiliation can be seen in the chart in figure 1.

All interviewees revealed that at an early age they were raised in a religious environment, taught a creation narrative, and were heavily influenced by a particular family member. For the pastor, a fascination with the sky was introduced by his mother, while his ‘traditional Christian’ upbringing greatly influenced his worldview and eventual vocation.[13] The astrologer confided

the one person who shaped [my own personal cosmology] would have been my great uncle…an avid lover of physics, and avid student of the Bible and also a practicing astrologer … a lot of things that ended up sticking to the wall were based upon my relationship with [him].[14]

These early Christian teachings developed into deeply held worldviews for the pastor and the astrologer. From similar beginnings, the other informant’s personal cosmologies developed along vastly different trajectories. The astronomer, while raised with ‘pretty strict religious influences’, now approaches everything from a purely scientific outlook without adopting a ‘specific set of beliefs.’[15] The Buddhist relates that his personal spiritual journey started with a loss of faith in the Judeo-Christian tradition based upon observed hypocritical behaviours of a grandparent, which set off a long investigation into all things esoteric. ‘From Shamanism, I went to Daoism’, he recalls ‘and from Daoism I went to Buddhism, and that’s where I stayed.’[16] He recalls a college friend who ‘was a devout Buddhist who also had grown up in the Christian faith’ who ‘helped [him] along… like a mentor.’[17] The psychologist’s path led from a similar rejection of an early Catholic upbringing- likened to a rejection of Greek myths- in favour of the cosmology taught to her in the public-school system. Yet as an adult, she found that, psychologically, she ‘had spiritual feelings and wanted something to do with them, and began searching for a spiritual home’.[18] She acknowledges ‘this notion that most faiths have a creation story’ and wants to ‘combine this with what [she] thought to be true about science’.[19] These informants’ revelations help illustrate the varied environmental, technological, psychological and social influences that Mathews claims are so influential to the development of personal cosmologies.[20] Furthermore, this study demonstrates that from similar starting points with similar influencing forces applied, individuals’ personal cosmological views can develop along completely independent and varying trajectories.

The question of cosmogony

‘How was the universe created?’ Karen Fox asks; ‘how does it work…how unique is… mankind…with questions this big, one almost has to rely on answers from…three disciplines- religion, philosophy, and science- each of which uses a fantastically different method to find an explanation.’[21] These are questions, not only of cosmology, but of cosmogony – a term that Hetherington defines as the subject, study, or theories of the creation or origin of the universe.[22] Both the questionnaire and the semi-structured interview prompted participants to describe their own belief as to how the cosmos came into being. Engaging the interview informants substantiated Fox’ claim about addressing the question of cosmogony- for the religious, scientific and philosophical methodologies adopted by the pastor, the astronomer and the Buddhist respectively, are indeed quite different and ultimately contribute to the development of quite different personal cosmologies.

Nearly half of the respondents self-identified as Protestant/Evangelical Christians, most of whom believe the cosmos was- in the words of one respondent- ‘created and set into motion by a sovereign and holy God’, with variations on that theme implying causality between the edict “let there be light” and the Big Bang.[23] Campion points out ‘Christian cosmogony is broadly… inherited from the Jewish book of Genesis, and the creation in seven days’, though acknowledges the ‘division between those who prefer to take this account metaphorically and those who believe it literally.’[24] Although the questionnaire responses were insufficient to elucidate any real division between a metaphorical or literal adherence to the text, the implications of the pastor seems to indicate that any such differences are incidental when compared to the central theme. He finds the Genesis account- stripped of the particulars such as the ‘length of a day’ which cause such contention, to ‘a pre-existing God that create[d] the universe’- makes sense to him.[25]In fact, even

some of what modern scientists would suggest [as a] possible means of … the existence of the universe… speaks in some way to the reality of a pre-existing supreme being that decided to make what he made.[26]

His religious methodology is an adherence to the creation narrative in scripture. However, as Romero D’Souza explains, ‘the Bible was not intended to be a treatise on cosmology as much as the story of God’s dealings with human beings.’[27]

If you take that back to the beginning, where it all came from one point, which is the big bang…does anybody know? Is there any evidence what happened at that one instant in time? Absolutely not.[28]

Using observational astronomy, cosmologists can see into the past yet ‘can’t see back beyond a few hundred thousand years after that supposed event. ‘So, was there a big universe that had collapsed and then [had been] reborn?’ the astronomer asks… ‘we don’t know.’ But he contends that the data gathered by studying cosmic microwave background radiation and particle physics of the early universe is starting to paint a cohesive picture. ‘I think we’re on to something’ he ventures. ‘but there [are] just some things that we might never be able to figure out.’[29]

The Buddhist, on the other hand, answers simply that ‘the cosmos is, and the start of it is not an essential question I seek to answer.’[30] The methodology he chooses to illustrate this philosophy is the paraphrasing of a Buddhist parable- that of The Poison Arrow. He poses a scenario wherein he is shot by a poison arrow but postpones treatment until all of his questions are answered – ‘Who shot it? Who made it? Where was the poison found? What venom did it come from? Why did the person shoot it?’ etc.[31] The precious time lost in pursuit of these inconsequential facts proves fatal. ‘Where we came from isn’t really all that important to me’ he answers, ‘it’s more [about] what do I do now that I know I’m here.’[32] The pastor, astronomer, and Buddhist informants each approach the question of cosmogony using methodologies from their respective disciplines- religion, science and philosophy. Their finding, unsurprisingly, range from a doctrinal surety to the testable hypothesis to musings on the metaphysical relevance of such beginnings.

The question of astrology

Respondents were posed with a hypothetical question: ‘if someone asked you if you believe in astrology, how would you respond?’[33] The Buddhist replies with little more than he does ‘not really ascribe to [astrology] as [being] much of a science’, a sentiment in line with Campion’s findings that ‘Buddhist texts have little to say about astrology but can be slightly antagonistic to it, partly because it…can be seen as a distraction from the simplicity of cosmic truth and the purity of the path to enlightenment.’[34]Likewise, the psychologist is ‘vaguely aware that some complexity exits’ in its application apart from newspaper horoscopes, but remains sceptical of its validity.[35] The astronomer notes that

we can calculate the exact location of Mars and Venus and Saturn in the sky… exactly where these planets were … a hundred thousand years ago, and… where they’re going to be… a hundred thousand years from now. If the positions of planets in the sky has any effect on my life, or anybody’s life, I see that as being highly coincidental… you would really have to stretch the butterfly-effect idea to make me believe something as…calculatable as that would affect my life.[36]

Similarly, Bart Bok and colleagues contend since the distances of these planets from earth have been calculated, it can be seen ‘how infinitesimally small are the gravitational and other effects produced by the distant planets’ and that ‘it is simply a mistake to imagine that these forces… can in any way shape our futures.’[37]

Most respondents who identify as Protestant/Evangelical Christians answered the question on a belief in astrology with a single word- ‘No’.[38] Campion points out ‘that Christianity has always struggled with astrology’, with those of a pro-astrology position ‘obliged to negotiate’ anti-astrology passages in the Old Testament, such as the prophet Isaiah’s challenge to Babylon- ‘Let your astrologers come forward, those stargazers who make predictions month by month, let them save you from what is coming upon you’.[39] On the other hand, he suggests ‘scriptural support for the divine nature of celestial omens’ may ‘fatally undercut’ an anti-astrology position.[40] For instance, the Genesis account relates that the Creator fashioned ‘the lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night’ and indicated these stars be used ‘for signs and for seasons, and for days and years’.[41] Although divergent opinions are reflected in the questionnaire data, the pastor points out that ‘looking at the historical aspect of the Christian bible you can’t miss the fact that there is astronomical or astrological stuff going on…there’s just no getting around that… when we talk about Christian eschatology…there’re signs in the Heavens, signs in the skies.’[42] Likewise, the astrologer argues that

the patterns in the heavens no more direct our circumstances or how we respond to them than a clock causes the sun to rise or set…time is time, and in that regard, I see the creator, God, as the master Timekeeper.[43]

She adheres to the belief that ‘astrology is humans’ method of noticing and studying [the] timing of the perfectly created patterns in the heavens’ and that God ‘has given us free will, but that he controls the timing of everything.’[44] Though in general most respondents did not offer even a casual endorsement of astrological belief, the most sympathetic respondents were, in fact, those of a religious leaning.

The nature of the universe and our place within it

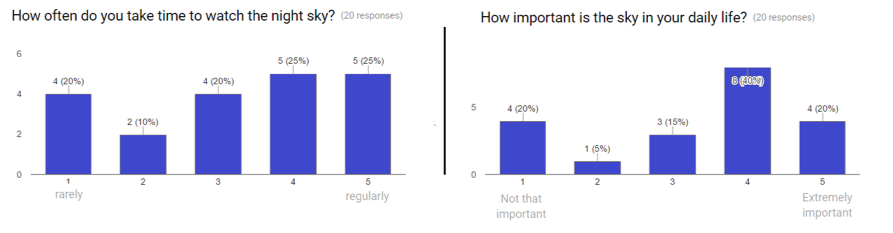

Questionnaire respondents were asked how often they took time to watch the night sky and how important the sky was in their daily lives.[45] In general, the respondents did spend significant time admiring the heavens and felt that was important, as shown figure 2.

The psychologist tries ‘to look and notice the moon each day… to know where it is in its cycle.[46] She feels very effected by sunlight, and reports feeling ‘oppression when we have a grey sky.’[47] The astronomer agrees that

‘from just a purely aesthetic point of view the sky is extremely important, but from the point of view of my profession…I’m an observational astronomer [and] we have a telescope here on campus that we’ve used to… discover some exoplanets… magnetic fields around other stars; I’ve used interactive binary stars… with mass transferring from one to the other as natural laboratories for studying the effects of stellar evolution.’[48]

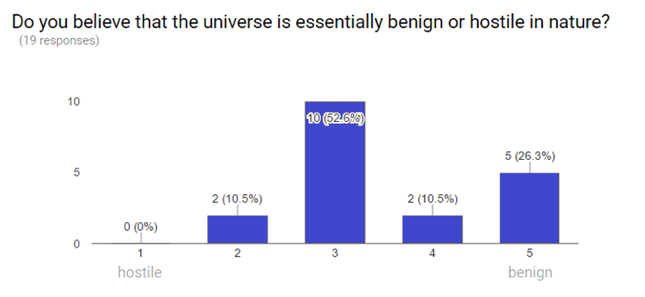

Several questions were posed concerning the respondents’ view of the nature of the universe. The questionnaire provided a definition of cosmophobia as ‘the unreasoning fear of the cosmos’.[49] This term was coined by David Morrison to explain feelings connected to apocalyptic beliefs such as the infamous Maya 2012 or other doomsday prophesies.[50] Participants were asked if they had ever experienced feelings of this kind, to which five out of nineteen respondents answered in the affirmative.[51] Campion explains that for cosmophobes, the cosmos is ‘essentially threatening, and something to be escaped…or dominated.’[52] This sentiment is also exemplified by Blaise Pascal’s admission that ‘the eternal silence of these infinite spaces’ frightened him’.[53] Conversely, the respondents were provided the Urban Dictionary’s definition of cosmophilia as the ‘overwhelming awe someone feels at the universe…not just how pretty it is, but the incredibly complex processes that made it what it is today.’[54] When asked whether they ever experienced feelings of this kind, seventeen respondents reported they had.[55] Campion, again, points out that cosmophiles are those ‘who believe that the cosmos is essentially good.’[56] It should be no surprise then to find when asked whether they believed that the universe was essentially benign or hostile in nature, the respondents answered overwhelmingly that they felt it was benign or neither (neutral), as shown in figure 3. Mathews explains that ‘a flouring community is likely to evolve a bright, self-affirming cosmology and a languishing community is likely to see the world in darker shades.’[57] If this assessment is correct, it can be argued this target group belongs to a flourishing culture, as the majority do not seem to believe that the universe is out to get them.

Figure 3: Histogram demonstrating that most respondents believe that the universe in neutral to benign in nature. Chart obtained from Google Forms, 2017

Additionally, questionnaire participants were asked what they believe is humankind’s place in the universe.’ Answers from the twenty respondents ranged from one extreme- humankind being ‘the center’ of the universe where ‘as God’s highest creation, we are to glorify Him’- to the other, with humankind ‘occupying a very small portion’ of the cosmos and being ‘completely insignificant’.[58]It would appear from this data that one’s personal cosmology is generally optimistic if the individual adheres to a religious worldview, whereas a purely scientific cosmology yields a more pessimistic worldview. Nancy Ellen Abrams and Joel Primack offer that

A living cosmology for 21st-century culture will emerge when the scientific nature of the universe becomes enlightening for human beings. This will not happen easily. The result of centuries of separation between science and religion is that each is suspicious of the other infringing on its turf…But a cosmology that does not account for human beings or enlighten us about the role we may play in the universe will never satisfy the demand for a functional cosmology that religions have been trying to satisfy for millennia.[59]

It is for this reason that Mathews warns that ‘a culture deprived of any symbolic representation of the universe and of its own relation to it will be a culture of non-plussed, unmotivated individuals, set down inescapably in a world which makes no sense to them’.[60] Fortunately, that does not seem to be the case here, as one respondent suggests it is humankind’s place ‘to improve the state of things around them and leave things better…than when they arrived’, although the psychologist voices concern that ‘we unfortunately have evolved to be capable of doing great damage in the universe and lack a common ethical system to restrain us.[61]Many respondents felt some form of action was required of humankind.

Conclusion

In summary, this qualitative study utilized an online questionnaire and participant interviews to a targeted group of twenty individuals in the American Northeast to investigate the concept of personal cosmologies. One aim of this research was to explore factors that contribute to the development of personal cosmologies, and within this target group religious adherence, secular education, and the mentoring of family and friends proved to be the most influential forces, each weighted differently depending upon the individual. Based upon their own worldview, individual informants applied various religious, scientific, and philosophical methodologies in conveying their beliefs as to the origin of the cosmos, which ranged from divine creation narratives to the Big Bang theory, to attempts at reconciling the two. When considering the validity of astrological influences on the lives of humans, opinions were split between sharp scepticism and a belief that the heavens are encoded with insights from a divine Creator. Topics of cosmophobia and cosmophilia were explored, and it was found that the target group believed the universe to be generally a more benign to neutral environment than hostile, which according to Mathews, may be indicative of a flourishing culture. Finally, opinions concerning humankind’s place in the universe seemed to be divided along lines of religious belief, suggesting that a cosmology which accounts for human beings is ultimately more optimistic than one that does not. This point compliments Campion’s line of reasoning, that if individuals are indeed formed in God’s image, they then serve as a reflection of ‘the creative force from which the cosmos is engendered.’[62] Such reflections, a Christian cosmology suggests, could not be devoid of meaning.

Bibliography

Abrams, Nancy Ellen, and Joel R. Primack, ‘Cosmology and 21st-Century Culture’, Science, New Series, Vol. 293, No. 5536 (2001).

Archaeological Study Bible, New International Version, (Grand Rapids: The Zondervan Corporation, 2005)

Bell, J., Doing your Research Project, (Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002)

Bok, Bart J., Lawrence E. Jerome, and Paul Kurtz ‘Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists’, The Humanist, September/October 1975, <http://psychicinvestigator.com/demo/AstroSkc2.htm>, accessed April 24, 2017

Campion, Nicholas, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, (New York and London: New York University Press, 2012).

Cosmophobia, < http://www.cosmophobia.org/>, accessed April 23, 2017

D’Souza, Romero, Christian Cosmology: A Manual of Philosophy and Theology, (New Delhi:Christian World Imprint, 2014).

Hennick, Monique, Inge Hutter, and Ajay Bailey, Qualitative Research Methods, (London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, and Singapore: Sage Publications, Ltd, 2011).

The Holy Bible, Authorized King James Version, ed. By C.I. Scofield. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967)

Mathews, Freya, The Ecological Self, (London: Routledge, 1991).

McMullin, Ernan, ‘Religion and Cosmology’, In Encyclopedia of Cosmology: Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology, ed. Norriss S. Hetherington, (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1993).

Pascal, Blaise, Pensées, trans. W. F. Trotter, (Chicago, London, Toronto, and Geneva: Encylcopedia Britannica, Inc., 1952) Section III: 206.

Urban Dictionary entry for Cosmophile, <http://www.urbandictionary.com/ define.php?defid=5784384&term=Cosmophile>, accessed April 23, 2017

[1] Norriss S. Hetherington, entry for ‘Cosmology’, In Encyclopedia of Cosmology: Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology, ed. Norriss S. Hetherington, (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1993), p.116

[2] Nicholas Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, (New York and London: New York University Press, 2012), pp.1-2

[3] John North, Cosmos: An Illustrated History of Astronomy and Cosmology, (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2008), p. 739.

[4] Freya Mathews, The Ecological Self (London: Routledge, 1991), p. 13

[5] Google Forms Questionnaire, questions number 1 and 2

[6] Eltica de Jager Meezenbroek, Bert Garssen, Machteld van den Berg, Dirk van Dierendonck, Adriaan Visser and Wilmar B. Schaufeli, ‘Measuring Spirituality as a Universal Human Experience: A Review of Spirituality Questionnaires’, Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 51, No. 2 (2012), p. 336.

[7] Bell, J., Doing your Research Project, (Buckingham: Open University Press, 2002) p.157

[8] Hennick, Monique, Inge Hutter, and Ajay Bailey, Qualitative Research Methods, (London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, and Singapore: Sage Publications, Ltd, 2011) pp.109

[9] Ernan McMullin, ‘Religion and Cosmology’, In Encyclopedia of Cosmology: Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology, ed. Norriss S. Hetherington, (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1993), p. 579

[10] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 7

[11] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 19

[12] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 3

[13] Interview with the pastor informant, question 1, April 10, 2017

[14] Interview with the astrologer informant, question 1, April 12, 2017

[15] Interview with the astronomer informant, question 1, April 17, 2017

[16] Interview with the Buddhist informant, question 1, April 19, 2017

[17] Interview with the Buddhist informant, question 1, April 19, 2017

[18] Interview with the psychologist informant, question 1, April 14, 2017

[19] Interview with the psychologist informant, question 2, April 14, 2017

[20] Mathews, The Ecological Self, p. 13

[21] Karen C Fox, The Big Bang Theory: What it Is, where it Came From, and Why It Works, (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002), p.2

[22] Hetherington, Encyclopedia of Cosmology, p.115

[23] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 4

[24] Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.164

[25] Interview with the pastor informant, question 2, April 10, 2017

[26] Interview with the pastor informant, question 2, April 10, 2017

[27] Romero D’Souza, Christian Cosmology: A Manual of Philosophy and Theology, (New Delhi: Christian World Imprint, 2014), p.110

[28] Interview with the astronomer informant, question 2, April 17, 2017

[29] Interview with the astronomer informant, question 2, April 17, 2017

[30] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 4

[31] Interview with the Buddhist informant, question 2, April 19, 2017

[32] Interview with the Buddhist informant, question 2, April 19, 2017

[33] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 16

[34] Interview with the Buddhist informant, question 3, April 19, 2017, and Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.121

[35] Interview with the psychologist informant, question 3, April 14, 2017

[36] Interview with the astronomer informant, question 3, April 17, 2017

[37] Bart J. Bok, Lawrence E. Jerome, and Paul Kurtz ‘Objections to Astrology: A Statement by 186 Leading Scientists’, The Humanist, September/October 1975, <http://psychicinvestigator.com/demo/AstroSkc2.htm>, accessed April 24, 2017

[38] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 16

[39] Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.171, and Archaeological Study Bible, New International Version, (Grand Rapids: The Zondervan Corporation, 2005), Isaiah 47:13

[40] Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.171

[41] The Holy Bible, Authorized King James Version, ed. By C.I. Scofield. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), Genesis 1:14

[42] Interview with the pastor informant, question 3, April 10, 2017

[43] Interview with the astrologer informant, question 3, April 12, 2017

[44] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 16

[45] Google Forms Questionnaire, questions 14 and 15

[46] Interview with the psychologist informant, question 4, April 14, 2017

[47] Interview with the psychologist informant, question 4, April 14, 2017

[48] Interview with the astronomer informant, question 4, April 17, 2017

[49] Cosmophobia, < http://www.cosmophobia.org/>, accessed April 23, 2017

[50] Cosmophobia, < http://www.cosmophobia.org/>, accessed April 23, 2017

[51] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 17

[52] Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.5

[53] Blaise Pascal, Pensées, trans. W. F. Trotter, (Chicago, London, Toronto, and Geneva: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1952) Section III: 206.

[54] Urban dictionary entry for Cosmophile, <http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?defid=5784384&term=Cosmophile>, Accessed April 23, 2017

[55] Google Forms Questionnaire, question number 18

[56] Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.5

[57] Mathews, The Ecological Self, p.13

[58] Google Forms Questionnaire, four responses from question number 8

[59] Nancy Ellen Abrams and Joel R. Primack, ‘Cosmology and 21st-Century Culture’, Science, New Series, Vol. 293, No. 5536 (2001), p.1770

[60] Mathews, The Ecological Self, p. 13

[61] Google Forms Questionnaire, two responses from question number 8

[62] Campion, Astrology and Cosmology in the World’s Religions, p.6